An essay that was previously published as “Being Ugly is a sin I am happy to commit.”

Listen to this essay below!

Hello. It’s a Friday in April and I am here to admit that I have lied to you all (again). I am here outside my favorite coffee shop with my stomach out for the first time in eons. I used to have a terminal addiction to crop tops and now here I am, hyper-aware that my stomach is out. For the better part of a year now, I have taken a break from being On Display. I’ve been out of the club. I’ve been campaigning on TikTok to buy my tribe some farm equipment, which is very different work than making a video of me looking cute so that hundreds of strangers comment and ask me if they know how gorgeous I am1. This is the longest time I have gone without my nails done, or my hair done, or a facial since I became someone always very Beautiful sometime in my teenage years. I am breathing differently now. I am here feeling like a feather floating back down to the body I left here on earth. It’s taken me months to balance out the reality of being naked and drunk for money with the reality of my straight-lace life as a content creator and a mental health professional— and lots of that balance has come with being honest about why that level of exposure felt so easy and natural for me.

Dancing didn’t feel odd at all… and that is the unusual part, right? Because if I am honest (which I am trying to be with you all these days), it’s because being semi-clothed for money wasn’t all that much different from the life I’ve been living since I was a child. The life I am still living. Content creation and dancing and modeling and public speaking have had all this instantaneous success for me because I am Beautiful. Truly. I didn’t really have much of an awkward phase becoming a stripper because so many things felt just like my first day of work— the gendered, racial, youthful performance of Beautiful Black Girlhood. The first time I walked a runway (12 years old); the first time I was on camera for the public (23 years old); or speaking on panels in college (19 years old); even interviewing for scholarships as a teenager (17 years old) making sure I was as Beautiful as possible. I have never been Ugly; I’ve never even been close. The one consistent parenting lesson I received from my mother (also dark-skinned, also disarmingly Beautiful) was how to always be the exception to the rule.

Last year, I released this essay that was originally entitled “Being Ugly is a sin I am happy to commit” and that’s a fucking lie. Not because I don’t like the Ugly things about me— I cherish them. It’s a lie because I am so, so far from Ugliness structurally. The reason I cherish the ways my body is not Desirable is because it is a relief. I have been desired since I was a literal child. Now, 24 years old, is the first time I have physical traits that could come under structural critique. My breasts wrinkle like my mother always warned me they would if I didn’t soul-tie myself to bras (and then I started swinging from a pole topless for a living, lol). They sag and swing now and don’t sit directly under my chin and it’s relieving. Maybe (maybe) that means I might be left alone a little bit more. The relationship I have to bits of me that are Ugly are tender and kind because the world still bends at my touch. I am disarmingly Beautiful and I know that. My survival has, at times, hinged upon me knowing that and using it well. I have no genuine conception of what it is like to be regarded as “less than” in this world because of the body that I move in. “Being Ugly is a sin I am happy to commit” is a cute title and a cute idea but it’s not… actually like I have the choice. None of us have the choice. Sin implies the intentional decision to deviate from what is good, what is righteous, what is holy— and while that is an accurate way to talk about the cult religion of Beauty in this society, short of intentionally disfiguring myself… I don’t really have the option to deviate. I am stuck here, up here, the exception to the rule and, simultaneously, the shining, shimmering proof of the rule itself.

In Threadings. the newsletter and podcast where we explore Black feminism and Love studies and other things that hold me together, we’re spending some time conducting a strong inventory of the self. I told you all this episode would cover the self that is my physical person, and that led me back to this essay. The first iterations of love I have for my body were uncomplicated because I have always had a body that did what I asked. I was not interested in being Beautiful (at all) until I understood just how much opportunity was available to me should I commit to marketing myself. I remember distinctly the teenage years of constant and honest appraisal: watching my body change because of puberty, because of sports, because of food insecurity, because of self-harm and willful neglect and noting how I slid up and down the ladder with the changes. I dedicated at least twenty minutes of mirror time a day studying myself and playing to my strengths or intentionally punishing myself. I had so much self-loathing and such a strong death wish as a pre-teen that I intentionally stopped brushing my teeth because I knew it would make me Uglier. I thought I deserved that. Relatedly, I was also getting breasts at the time— big, ripe breasts jutting out of my chest that I did not want. There’s no PG way to talk about how visceral and traumatizing it is being a child walking around like that. Catcalled and the catwalk for the first time at twelve years old. Of course, I hated my breasts. I think I also found some relief in having something to repel the new way people looked at me. Gazed at me, now. I was already making negotiations about what parts of Beautiful Girlhood I would participate in and what parts were too much to reconcile as a child. I have not stopped negotiating. I’m sitting here as an adult recalling how white strangers would reach out to touch me as a little girl, how visibly awed they were at me and my mother and sister for being so unambiguously Black and so undeniably gorgeous.

The top of the Beauty hierarchy is not a Blessing; it is not aspirational; it is the farce of pretending that being chosen stands in for the loneliness of being a status symbol. I return to the text “In The Name of Beauty” from Tressie McMillan Cottom to explore my body— this time rewritten with more honesty about what I am and where I fall.

Even if you’ve already heard the bulk of this essay, I more than encourage you to give it another listen: not just for the things that have changed or been added, but because reading and re-reading is so crucial to learning. Learn slowly and with repetition.

Let’s begin.

Studying the internal self requires the study of the body.

My first assertion is that I believe in my own consciousness with the same tangible surety that I have in my Body. I think contemporary thought, especially Western contemporary thought, likes to imagine the Body as a secondary characteristic to the almighty mind, or the poetic soul, or whatever light of consciousness you have buzzing inside your meat sack. The idea here is that you are the thing that inhabits your human form, and I… think that is a load of fresh horse shit. Literally. Steaming, fresh on the barn floor, horse shit. How am I more of my mind than I am my body? Who decides those rules? Who benefit from us thinking we are, somehow, better than or divorced from or higher than our bodies? Why is it so common to hear that our bodies are “flesh prisons?” What does it say about the world we live in if we think in carceral terms about our physical manifestations of self?

I fundamentally reject this. I think I am as much my body as I am my mind. I assert this with a couple background identities: as a therapist, as an avid reader, as a mind who is sharpened by my soft and sinewed body, and as a body who is compelled and collected by my mind’s expansion. The second unit of Threadings., formally known as The Garden Spaces, continues on with this essay that seeks to explore the human connection I have with myself: the union (or dis-union) of the presence of my Mind wrapped up neatly in my Body.

The Body (n): the physical self which respirates. The flesh and bone that houses every thought an omnipotent narrator could never find the words to say. The method we first interact with the world: our bodies in same space. Skin to skin contact. The physical thing which feels through being touched and seen and held, being cast aside or hit or isolated.

I argue that I am as much my body as I am my metaphysical mind, my floating soul, my otherwise packaged and perfect ideas of self. Whatever I think about myself, The Body been here, breathing. Long before my mind ever learned to grow and keep growing, before my mind knew anything at all, there was the Body, respirating for us. Communicating for me. The first self that ever was (and likely the last self I will ever be) is my Body. My mind will have withered and been gone and my Body will be here, breathing. If that’s the case, I believe I would do well to study the physical nature of human connection, and I would like to take you all with me as I try to wrap my mind around the fact that my Body does not need me to think all these self-important musings of what I am or am not. I am someone who imagines that I am in community with myself. How do you talk about the intimacy of the self without The Body? About feelings, which live in the body? About sex and the politics that sex comes wrapped in? How do we begin with the mind when The Body is the one that held us first?

I have a couple questions for us at the start of things.

(1) how does the internal self co-exist with the Body? In what ways do they inform each other? Are they ever completely separate? Is that even possible? And if it is possible… do I want that? What do I gain from conceiving of the mind and the body as independent forces? And if I do not stand to gain… who does?

(2) How does my Body inform conception of self, internal and external? How does my body exist and interact with world systems? How can I create safe spaces for my body, both personally and within community? What does that safety necessitate?

I am going to attempt to answer those questions by reading, writing and talking. I will be learning in real time; if you need to orient yourself to this online space, or you need more clarification on what that means for me as someone who makes art on the internet, I recommend listening to or reading the essay “The Garden Space: an Introduction.” But this I will say at the top of every unit, so we can all be on the same page about what to expect from one another.

I am engaging in the vulnerable process of learning in real time, and that means I must be in conversation with three entities: myself, my peers, and my teachers.

I will introduce myself:

My name is Ismatu Gwendolyn and I am committed to learning and feeling through the sticky nature of human connection— the study of love, or the lack thereof. I have scholastic dedication to African-American studies, global health, clinical social work and poetry, and I have academic histories and roots at Northwestern University and The University of Chicago. I am an information anarchist and I act on that politic by learning, growing, and sharing what I learn, both on my TikTok where I do personal + political education, and most especially here with you all, at our shared plot in my Garden Space.

I will address my community:

True learning attunes new lessons to the beat of oneself and one’s community, which is why that learning in public bit is important. If you are here, week in and week out, I consider us to be in community with one another as we learn. Grab a chair. Bring your friends. You are free to ask me any questions or leave me any comments, if not on the Threadings. comment feature, then with replies to the email newsletter or comments on the podcast. Thinking in isolation is only cute for rich white men geniuses: I need to knitted in the thoughts of others like a quilt. Please: don’t make this a one way conversation.

I will express gratitude and invitations for my teachers:

Theory is a guiding light for me in the constant wade and waves of the world, so I’m picking up some handfuls of North Star direction from a couple impeccable scholars: Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom with essays from her book Thick: And Other Essays, which we will be discussing at length today (and for a separate podcast episode, Dr. Sabrina Strings with her work Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia, excerpts from Dr. Deborah Gray White’s Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South and Da’Shaun L. Harrison’s seminal text Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness). Thank you all for helping me give words to the feelings I have about this body that makes a fool of me for trying to make sense of it.

Notes from “In The Name of Beauty”

Section One: I am Ugly.

Tressie McMillan Cottom is not the first writer to postulate on Beauty as a whole, however she is the first to imprint her words on my person. After I read Thick: And Other Essays, I felt like I had gotten a tattoo. I was in my final year of undergrad being unsurreptitiously pushed into the “real world” (the world which collapsed around me both personally and politically, since I graduated in June of 2020). Sitting in a swivel chair of a too-cold classroom, I found Dr. McMillan Cottom to be impressive— not in that she has a resumé or writing prowess that I found formidable (though that is also the case); I mean that she, through her work, was able to touch me and leave a mark. Her thoughts, her pen, her deep understandings of the conditions we were navigating and most especially, the apologies she did and does not make stuck themselves into my brain and pressed. I am changed and I am grateful.

McMillan Cottom opens her essay “In The Name of Beauty” by revisiting words she wrote that made Black women angry. She got some deep hearty church girl mmm’s out of me, reading the entry into the analysis; if I did not relate to those sentiments then, I most definitely feel the weight of the wrong people angry at you the way I am on the internet now. The essay recounts, reflects, then reconvicts the reader about multiple assertions, however I think the one people took the most issue is as follows:

I, Tressie McMillan Cottom, am Ugly.

She used the word unattractive here, but unattractive and Capital ‘U’ Ugly mean the exact same thing. What is not Pretty is Ugly, and there is really not in between. And hoes were mad. Hoes across racial, economic, generational, and gender signifiers were mad mad. A simple statement (I am Ugly) provokes equally simple but uncomfortable follow up questions:

Why?

And, a bit further:

If you are… then what am I?

Ah! Now we’re talking.

Of course, I encourage you to read the essay for yourself. If you would like the text but cannot afford it, or if you would like to sponsor the cost information sharing for someone else in Threadings., email me at ismatu.gwendolyn@gmail.com. No reader left behind.

The question of the standard (who makes the standard, or what makes the standard) is pretty easily digested: white landowning men created means of measurement for what makes a marketable and effective wife to continue and expand an imperialist white ethno-state. A racist and genocidal Beauty standard follows suit. That part is not hard— or if it is, I have a lovely TikTok series explaining the basis and effects of Capital ‘B’ Beauty. The playlist is linked here in the newsletter.

Standards of Beauty are visual and visceral. Outright stating “I am ugly” acts as sacrilege against the holy and rigid performance of wielding and coveting Beauty. It is swiftly corrected. The charges brought up against the author for breaking the Beauty Rules include but are not limited to: attention seeking, fishing for compliments, self-hatred, and misunderstanding the intentions of benevolent white people when they reach out to touch you, a stranger, as if you are a very soft, rabies-free pet monkey. Look at the manner those reprimands minimize and individualize the claim. Dr. McMillan Cottom made no assertions about her personal self-esteem, or her ability to date, or what others must think about her. She stated a structural fact: I am outside the flowing cornucopia of marketable Beauty. To be unPretty, to be a Have Not, is to be unnattractive. Ugly. That is a neutral and evidenced sentiment at worst.

A common counterargument usually crops up at this time— the but all. “But,” a long haired, doe-eyed darling will sigh with one single tear clumping on their bottom lashes, “but… don’t we all suffer under these rigid and punitive beauty standards?” Yes, beloved, we do. See McMillan Cottom on the fifth page of this essay: “That is the violence of gender happens to all of us in slightly different ways. I am talking about a kind of capital.”

Stay with me here. From the same page:

Beauty isn’t actually what you look like; beauty is the preferences that reproduce the existing social order. What is beautiful is whatever will keep weekend lake parties safe from strange darker people. (page 5)

All capital is world-making. Beauty is access to that world (but it does not necessarily mean you hold onto that capital). Beauty is a kind of capital that exists as a ticket into the door of a paradise— a picture perfect pool party filled with the best liquor, the most gorgeous swimsuits, ringing laughter floating above the most beautiful people you know like beach balls. It’s perpetually golden hour. It smells like sunscreen and sleek, perfumed, oiled bodies brushing up on one another, and fruit trees blooming, and you are standing outside the wooden gate perpetually looking in. And you are meant to. That is the designated place of the Have Nots. In fact, the most you will ever be if you are an aspiring Have Not is an exception to the rule.

Beauty is the tool of whiteness. And what is that? What is whiteness again?

Whiteness is a violent sociocultural regime legitimized by property to always make clear who is black by fastidiously delineating who is officially white (McMillan Cottom, 6).

It makes sense then that such an amorphous party of people would need tools able to shape-shift alongside them. Whiteness constantly cannibalizes new groups to maintain their power. Beauty is the perfect weapon. The nebulous nature of what could be considered Beautiful means that you can convince people of happenstance. You can sell them the plastic lies of individual preferences, of coincidental trends. You can make the brainwashing incredibly easy to swallow— tasty even. Beauty in white supremacist world-making is directly tied to worth. If the task is to convince a public of pre-defined Haves and Have Nots that participating in this compulsory beauty pageant for basic societal safety is a worthwhile task, you do need to convince them they could win. This essay, as well as our text from Dr. McMillan Cottom, speaks to this exact paradox: these two ideas, unique blessing and earned reward, are antithetical to one another (14).

This is where I have to stop and insert myself. I, the author of today’s podcast essay, have never known life outside the pool party. I owe you that honesty: I am writing this from the shade of a wide-brimmed hat and oversized sunglasses, sipping the champagne leftover from the stack I just made letting a middle aged man breathe hard at the sight of my bare chest. I am writing to you from the reality of being favored and being exploited by the people that let me in here. I am only here if I am okay to be oiled up and topless— and what is okay to a twenty-two year old mountain girl trying to survive by herself in the Big City? What is okay if these same men ogle me anyways, at my university, at the dentist’s office, off the street?

I do my best to pretend there is a choice. I sip my champagne and decide I do not mind.

“If I knew to be cautious of men, I did not learn early enough to be cautious of white women.”

Definitionally, Black women are not Beautiful except for any whiteness that may be in, on, or around them (and the anointing marks whiteness can include: wealth, slim features on the face and body, smoothness of flesh and hair and color, lightness in the eyes or across the skin. et cetera). And white women need it to be that way, to convince themselves the work of Beauty is worth it. Desirability is a language that changes in between cultures and circumstances and you (the Beautiful, or the Wanna-Be Beautiful) are expected to always be fluent. In fact, it is vital that you are always fluent. Much of your safety depends on you ensuring your body is the right kind of body for the space— or if it is the wrong kind forever, that it is restrained and punished in the correct way and publicly. If you are Ugly you are expected to be sad about it, and loudly. How do we know who the winners are if the losers aren’t weeping, like the end of Mario Kart? The performance of Ugly shame is so delicious to Pretty People that they [we] might reward you for it; it is almost the same sweet precarity as actually being marketable. Think Game of Thrones, Mr. Johnson swinging his keys level of shaming. That performance, the “it’s so sad and awful to be an ugly loser” thing that we expect Black people, Fat people, kinky-coiled people, disabled people (etc.) to do— it’s necessary in the game of Beauty to validate the winners. It assures them [us, we at the top] that the restriction and the suffering that comes emptying out your guts (literally and metaphorically) to win this game is worth avoiding the shame of being Ugly. And what do you win from being at the top? The pursuit of Beauty transforms the Body in its breathing entirety into an echoey status symbol. And the constant apology, along with the public spectacle of it all, acts as an eternal and internal whipping post. It means that even down to the littlest basic human actions— finding seating, eating a meal, dressing in warm weather, existing outside— The Ugly are meant to flog themselves. You are meant punish yourself for being visible while Ugly (or others will do so for you). Beautiful people can then say, “…well. At least I can trade my suffering for money and validation.”

God help us.

And that’s the game! We all suffer and some of us get a pool party. It must be that way, or at least be thought of that way— democratic and able to be earned. You cannot break the rules of Beauty Charades by just stating the obvious, like Dr. McMillan Cottom did. Otherwise… game over. Beauty instantaneously becomes revealed a commodity, and not just a commodity but a lottery, distributed unequally and at random. “If you did not earn beauty, never had the real power to reject it, then you are as much a vulnerable subject as I am in your own way.” (12-13)

Fuck. Exactly. Let’s keep going.

Section Two: If ya status ain’t hood

Here is that same long-hair doe-eye song. “But Lupita! But Naomi!”

Yes, darling. I know you see them. The glittering dark-skin swimming like flies in milk among the rest of the shining Beautiful people. I’m there, waving at you, pretending to be having a good time. Or maybe the pool party you covet access to looks different entirely. Maybe it smells like edge control and juicy couture and a fire hydrant raining down fresh summertime relief. Maybe there’s a criminal amount of bass. There is most definitely a criminal amount of ass. And even here, still—Bodies. Laughter floating above the most Beautiful people you’ve ever seen, half of them with golden teeth.

Enter Beauty’s younger sister, cut with baking soda: Desirability.

Indulge me in a short passage.

I am dark, physically and culturally. My complexion is not close to whiteness and my family roots reflect the economic realities of generations of dark-complexioned black people. We are rural, even when we move to cities. Our mobility is modest. Our out-marriage rates to nonblack men are negligible. Our social networks do not connect to elite black social institutions. When we move around in the world, we brush up against the criminal justice system. I am not located at the top of hip-hop’s attenuated beauty hierarchy. I am, at best, in the middle. As Michael Jackson once sang, when you’re too high to get over it and too low to get under it, you are stuck in the middle and the pain is thunder (12).

Look at where Beauty is located here: not just in physicality. Not just in or on my body. In proximity to wealth— which we all know is proximity to whiteness. To the right kind of whiteness. There is nothing marketable about being Black and rural, unless you constantly apologize for it (which Dr. McMillan Cottom, for all the accusations of low self-esteem, never does).

I am here in this text too: rural, poor, generationally, personally, and spiritually From The Mountains. I will be honest again in telling y’all that the party I always long to be at is this one, where I am desired by men I might actually like to fuck (or at least like the performance of fucking). This was the first few morsels of my twenties, relishing this invite to the After Party. I spent a good while here pretending this kind of Beauty Capital was Different (™) and better and was something fun. Picture me: a tie on, too small triangle bikini and shorts with the ass out, still in my iridescent glitter Pleasers, letting somebody with a whole row golds talk me outta my drawls. I’ma tell you now, it’s not a long conversation. I keep spilling Hennessy on my titties. I keep pretending like it’s fun and like it’s something I like. I only like being desired like that when it’s naked and out in the open, like a live wire, instead of white men telling me in a hushed tone they’ve never touched a Black girl before. I only like being desired like that by Black men with stacks in their back pocket and a steady, unflinching gaze at me. I like that when I am drunk. Money makes me horny. It’s why I always did so much better in “those kinds” of clubs. It’s why I had to stop drinking— to realize how much I only liked that shit when I was drunk.

We examine the Beauty of whiteness: featurism, hair color and texture, skin coloring, sure. Of course, those. But also: wealth. The right kind of wealth. Wealth in capital. Social wealth. The correct type of upward mobility. The “right” company, which varies depending on the culture. The appropriate accolades: enough to be impressive but not competitive. Those will all get you social capital, a different kind of Beauty, to be exchanged for the correct kind of attention, and rewarded with pedestals and a plexiglass cage where folks can ooh and ahh at you as… a status synbol. Where white folks will have my Black ass in a zoo, Black men of means keep me on an invisible leash, two paces behind them. As a Have Not, you are meant to assume that being desired is better than the shame and isolation of complete, sneering rejection; a plexiglass cage is meant to be more appealing than dreary iron bars and shackles. The best you can be is Desirable. Beauty and Desirability are not necessarily synonymous, but they do hinge on and produce the same sort of swinging, strange fruit.

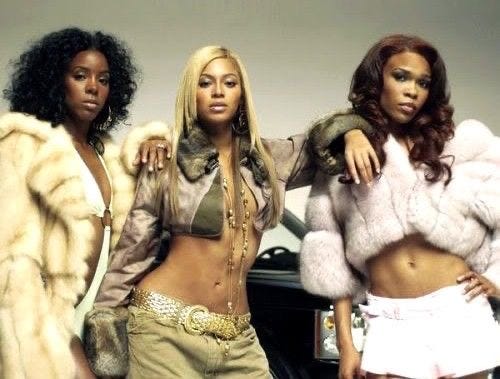

I want to note our differences here, between me (the author of this essay) and Dr. McMillan Cottom (the author of the text we’re soaking in): I am pretty near the top of hip-hop’s attenuated Beauty hierarchy. I know so because I am constantly in professions where I make money of the way my face and body looks. I know this because I routinely made double the money when men of particular demographics come into my club. If I am showing up to shake my little ass and go home, Soldier by Destiny’s Child is a wonderful rubric for me. What do the Black women in that music video look like? The ones with shining bodies, the stars of the show, the ones we are clearly supposed to be looking and looking at? What building blocks of Beauty do they have? Yes they are not white, but of course they’re not— are they attempting to be palatable to the regular-degular white folk? Who do they want licking their lips?

Black aesthetics are still able to garner and secure capital, specifically off the labor of Black women’s Beauty Work. McMillan Cottom notes that too— not to be left out, we are ingenious. We reinvent and redefine and work and work and work to make space for ourselves to be considered Beautiful, and yet the people that lick their lips and sign the checks are still… the men.

Oh, the men.

Beauty must appear to be democratic for two reasons— firstly, to convince the well-meaning but ill-informed voters that “their vote matters” (lol). McMillan Cottom already stressed this point when considering why white women are so enraged by her calling her own Black self unattractive, as if she cannot taste the water we swim in. The holiness of the vote is also enforced by the Black women that are mad mad at her because they have no desire to be Ugly by association. This is the cis, thin, straight plight of the Black women, the “why can’t we just expand Beauty standards?” Those of us that are close to the top of the pyramid hope we can be the exception, still desired by all. We ask, “well, why can’t we be included in the standard?” and never “Why is there a standard issue of the way a body should be at all?”

The theatrics allow us to keep the veil between worlds up; one where we know what we are and are not, and one can pretend they [or we] can earn Beauty (thus: earn access, worth, and safety) if they simply try hard enough. And that feeling of deservedness is powerful. It’s the grease that allows you to capitalize and weaponize the Beauty that you know is rotten and stinking. When you are able to say, “I earned this,” with your money, in the gym, by your makeup skill, via the man that chose you, whatever— it’s all the easier to cast aside those who cannot or choose not to do the work. You get to do that and pretend you are not making some ugly negotiations. I want us to be so fr.

In my original publishing of this essay, I say a quick “ah, but I digress” and move on. But I want to be honest. Those of us Black girls (or Black raised-as-girls) that had a chance of being thee exception, we go through intense training on how best to market. We are trained on poise, thought, presentation, perception of self that is honest so that we can know how best to market ourselves. We are taught the rules of the game and given the license to abide by or break the rules of Beauty based on what we want in this world. I remember my mother constantly giving me feedback on my outfits, my cultural markers, my makeup (or lack thereof, because I have never worn makeup [or earrings] on a regular basis and it makes her so mad). I thought these lessons were useless and dated, the relic of her growing up in times where a woman could not have a bank account without a husband. She had me on this ticking clock for marriage at 25 that I tuned the fuck out. Her Beauty lessons felt useless… until I started interviewing for college. Until there were full-ride scholarships to some of the best schools in the country on the table. When I had to sit pretty and seventeen in front of white men that were often-times obviously disarmed that I was pretty, then marketing started to matter. When I realized how much power I had in being a young, classically intelligent, well-spoken, pretty Black girl. There is a certain amount of Beauty capital available to Black girls that read, write and speak. White folks will always cut a check for the next Morrison. We’re the beating heart of art and academy and they know it. But don’t let you be pretty. You read and you’re pretty? Oh my word.

So this is what I’m saying: I don’t get to just digress. I am telling you that I started making negotiations between what I knew to be fair and the life that I wanted when I was seventeen and plotting a way out of the suburbs of Arizona. People around me were dropping left and right from drug abuse. I had high school classmates dying of heroin overdose, robbing their own parents and parents of friends for more money. Raiding medicine cabinets. Everybody medicated. Suicide was common. Death from driving under the influence was common. We were wasting away and (little known fact) I almost did not graduate high school from how much poverty-induced absence I incurred. Those bitches wanted to lock me up for juvenile truancy. I was about to not graduate high school. Yes, that is when I stared perfecting my eyeliner. That’s when I figured out how to do Disney Princess makeup and how to slow down when I speak, how to pick dresses that made white folks with money, with recommendation letters, and with opportunities overlook the stench of poverty. The only reason I was able to graduate high school and go to college was because my principle (who knew me as a sweet, pretty, church girl spelling bee champ) called the school district on my behalf and told them to lay off. It was because my very Beautiful mother stayed bribing the attendance ladies with her insanely good meat patties. I didn’t even have to go to trial. I fundamentally don’t know that it would have went down like that if I were some kind of structurally Ugly— if I was a fat Black girl that reads. If I was a disabled Black girl that reads. I was a pretty Black girl that reads and so I made it to elite college and kept negotiating.

We are still negotiating, me and this body that breathes. We’ve been doing this little dance for so long, I can’t tell what’s a choice and what’s not. I don’t have any judgements to make of myself. For a lot of us here, near the top but not quite, what choice do we have? It don’t make it right. It’s never gonna be right— what it did was make sure I lived to adulthood. Beauty is precarious; it keeps me alive while also keeping me drugged. It took me… *checks watch* like five months in the club circuit before I started Doing Drugs (allegedly). I am so happy my Depressed So I’m Doing Drugs phase happened in graduate school. Beauty bought me a ticket out of drugs for survival and into a life of doing drugs with millionaires. True class mobility.

Okay, now. Now, I digress. I want to be honest about the ways I benefit from Beauty capital, but it’s a double-edged sword for me. The other group that benefits from the performance of choice are the world-makers here: the men. The people that cut the check. We vote and we walk in the Beauty pageant so that the oligarchs in charge can look fairly and judiciously elected. And then— then! When “reworked” or “more inclusive” Beauty standards emerge, it’s just a coincidence that they happen to have their subject in swimsuits, drinking liquor laughing, belly up for the men who lick their lips. It is still marketable at finest, and if not marketable, desirable. Consumer ready. Safe to eat right out of the packaging. There’s a reason I only like it when I’m drunk.

And so we giggle at the grills and float, happy and full of alcohol, and we never think about the position of status symbol: void of true power, only being loved with possessive conditions attached. We’re not quite rendered speechless; of course, you can make a couple statements with your fabrics and your patterns. But you are, in large effect, a purse. Fungible items. Raw materials to be used in the dreams of the powerful. Your weighted creation doesn’t stretch further than what the checks think is Beautiful, and you might even be content because at least you are not outside the party, standing there, sweltering, sniveling. Ice cream melting. Alone.

That’s what I can say, right? That at least men want me.

Ha ha.

Actually! I forgot myself. We on this inside of this party will never say that. Never out loud. Because then what— I’m hot, you’re not, game over? Where is the longing in that? We are meant to think that silently and smile to ourselves and then continue on in the charade. Of course, the Haves are not in paradise, they are allowed access into the paradise of the people that made the world for them— but at least they are inside! We take up a chorus of “self-love” and “inner peace” as the people that chose us create conditional safetys and kisses on the forehead. Material and emotional reassurance for us, “self-love” and “beautiful inside out” marketing for the Have Nots. Yes, it is all marketing, even still. You simply cannot be Beautiful and openly mean-spirited or out of balance; in all things, you must be something to admire to. We shimmer louder so that “inner glow” gets added to the worksheet called Ways to Apologize for Yourself. The most stunning thing you can do as a lady of leisure is give the Have Nots some work to do.

This is also the social theory behind why “I can take your man if I want to” is an insult. I am calling you broke in Beauty capital. Just like a pumpkin only turns to a carriage under the right benevolent wand, Beauty only turns to capital under the right kind of attention— the attention of the folks in charge. Catering to the powerful, the most resourced, the most visible gives world-makers the ability to decide what is and what is not pleasing overall. It makes sure the same people are throwing the same exclusive pool parties. The dance of standards will never be equitable: the reason you establish a norm in the first place is to ascertain who or what is deviant. Even more terrifying is considering what the menfolk who made up or modified the standards in place want from Beauty.

What’s pleasing to them is power. They make the pinnacle of Beauty conveniently synonymous with what helps them concretize their world-building power. They will cannibalize you over it. The Blackness we Pretty Black Girls have in common with the men that lick their lips means so little. Whatever power we get from being desired is still not ours to wield. Power never belongs to the status symbol, it belongs to the person wearing it.

Naming that you are on the outside of these pool parties, that you are trapped in a Desirability Zoo to have the right kind of attention gawk and throw dollars at you, that is not self-hatred. Dr. McMillan Cottom does not internally hate herself by stating what is obvious to her. That is an honest assessment of self position. Self-hatred in the context of Beauty is looking at a Body, any of our breathing Bodies, and thinking, “We must have a standard with which to measure them by.” Why would we ever need this? What compels us to create a norm for something that was here before we thought up cages for ourselves and our neighbors? Who benefits from us thinking our bodies are subordinate to our minds and that our mind’s preferences are always pure? How easily might it be to brainwash a populace that is convinced they alone are too smart to be duped?

Beauty is not good capital, as stated in “In the Name of Beauty.” (No capital is good, but that’s an entirely different essay). The fruits of your labor, your Beauty work, always result in violence— for yourself, for someone else, for both. To climb up higher and safer in the Beauty tree you eventually have to kick the chair out from someone else to scramble up. Yes, you do. There is no getting around it. We might not always have a choice, but I want us (the Pretty Black Girls) to be honest about the conditions we’re in. Be FR!!! In investing in Beauty, you will always be negotiating with the death machines that chew up the Undesirables. And the best, the best, the best you will get from that plexiglass chamber is being desired by people that would kill you if they didn’t want to fuck you so bad. We were one flat nose, one wrong family tie, one degree, one cup or jean size away from swinging down there with the rest of them. You didn’t earn shit. The game of Beauty is always a negotiation and you will always, always end up at the end of someone’s beating stick. And maybe you like that. Maybe you have a kink for pain— I do. I’m not here to judge and I’m change your mind. I’m just tryna call a spade a spade. I just want us to be honest about what all of this costs of you, what it costs of me, how much it costs us.

Let’s return to the initial questions.

(1) how does the internal self co-exist with the Body?

Politically. There is not getting around that. The Body that breaths is a site of politic being enacted on or around or about you. Sex and gender politics occur in many ways— why do we always think reproductive rights? Why do we never think about Beauty, the politics of Desirability, of resource allotment an acquisition?

(1a) In what ways do they inform each other? Are they ever completely separate?

In my opinion, no. The Body and the Mind aren’t separate or distinct; the Body thinks and the Mind respirates too. I don’t think it’s truly possible to separate them. I do think our conceptions of self have been shaped by the world systems that swear to us there’s a difference. I don’t have anything to gain from the idea that I am more of a mind than I am a body— in fact, I think I make that distinction because it makes it easier for me to swallow how much Beauty rules my life.

And pretending I am a mind and not a body makes it easier to pretend I deserve this life I have. These life-changing opportunities that have been given to me, in no small part, because of Beautiful packaging. The sad reality that my body that breathes is reduced to being pretty tissue paper in this world. I don’t have anything to gain from ignoring that that’s the reality of things.

(2) How does my Body inform conception of self, internal and external? How does my body exist and interact with world systems? How can I create safe spaces for my body, both personally and within community? What does that safety necessitate?

The capital ‘b’ Body? My body reminds me that I will not always be under the thumb of Beauty. Previous to this year [year 24], I never dreamed of being old— mostly because I spent my childhood understanding I was unlikely to survive my teenage years. I have only recently begun to realize I do have a Rest Of My Life. My body’s unending desire to survive has made me understand the freedom that lies in aging. Like I said, my breasts sag a bit now and I breathe honest sighs of relief. They’re still desirable— my body (still) drips in sex and that’s what people see when they see me, whether I wear my crop-tops or not. Beauty and sex and supple skin and gold highlight. Fine. But the promise of old age is sweet in that I will one day be old and be able to fully belong to myself. Oh, to be cloaked in wrinkles and wisdom. To have aged past desirability.

There is no safety in Beauty. There is no safety for me; not while I look like this; that’s not a complaint, it’s a fact. None of us are safe here. It feels good to be honest about that, that every interaction I have is colored by people liking me, or being predisposed to love me or find me valuable or revile me because I Look Like This. There’s no safety in that. And more than that, I can’t really ever be the one to create safety for others who are punished because of their body. I am regarded as Beautiful everywhere I go. I am Beautiful “despite” the unambiguous Blackness. I can’t spread any safety in the position of being the exception to the rule. It’s freeing being honest about that.

What I can do is disrupt the game of Beauty by reminding everyone that sees me, loudly, that there is no deservingness in this game. I can ruin the fun of the victors that see their estheticians twice a month and still post bullshit like “it’s what’s on the inside that counts.” I can talk openly about the negotiations, the vulnerability, the isolation that comes with the biting “blessings” of Beauty.

And I can wait until I am old enough to see the Beauty melt off me like hot butter. I’ll have made my rounds and borne my children and hung up my heels. My breasts will hang down to my knees. I will look like my grandmother and rejoice. One day I will be free.

ismatu gwendolyn.

of course I do. Come on now.

24 | There is no safety in being Beautiful: reflections from a life spent On Display (™)