an essay nearly entitled, “a story which returns me to my own brilliance.”

The strangest part about terminal illness is how often death comes for a peck on the lips and nothing more. A few weeks ago, I flew home to attend my mother's final affairs. Now we sit, smoothies and champagne glasses, watching a movie to spend time together. It's sunny this Tuesday. Here are reflections from Invisible Beauty on Bethann Hardison, from both me and my mother.

This documentary made me eat my words about Representation Politics.

When I watched Invisible Beauty by myself some months ago, I was in Badalona, Spain, surrounded by white folks (and unfamiliar whites at that), in the bell jar we writers can sometimes trap ourselves in to rot and ferment properly. I was not having a cute day. This film made me feel so… loved. Remembered in a way that I had never felt myself before. I was floored by how much I had never considered what a life of negative space would really feel like– at once, nostalgic and sympathetic for realities I’d not personally experienced. I am twenty six years old, meaning: there has never been a day in my young adult life where the Negro was not in Vogue (word to Langston Hughes). Blackness within my lifetime reinvents culture as easily and as surely as the sun rises. We embody the new, the cool, the revolutionary so easily I often fail to remember the world has not always been this way.

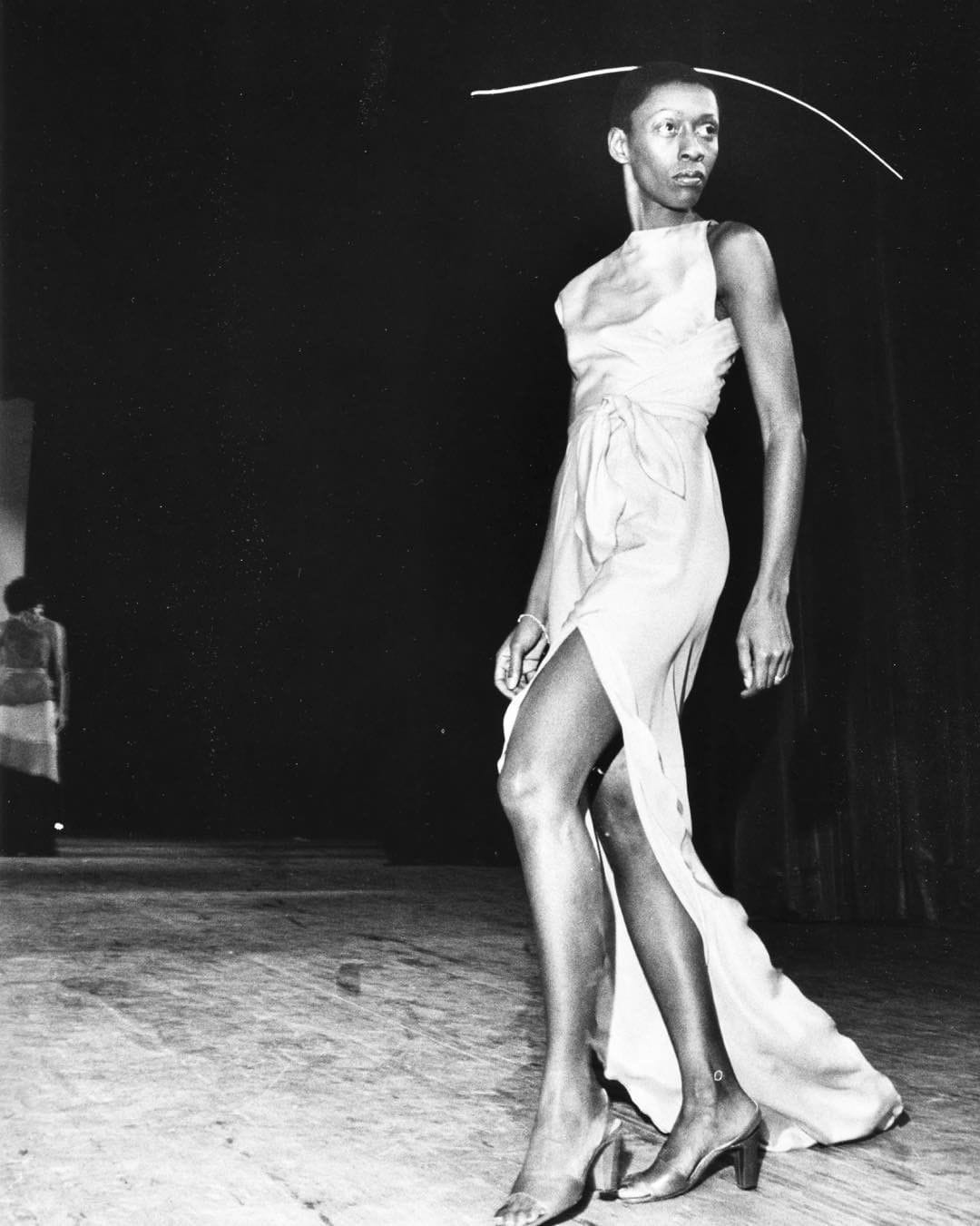

That work of archival acts as a gesture of love. Life feels obvious those living it every day. The decision to archive the tastes of the moment, to preserve the air such that those of us living in the Unimaginable After can feel what was felt, can see what we no longer have the perception for, is a gift. Bethann Hardison, in the making of Invisible Beauty, has gifted us the blueprints of her taking Black culture into high and white spaces– convictions that, over time, turned her into a visionary. Hardison became a model in the middle of her twenties after growing up in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, New York. The upbringing she had between her parenting and her schooling adorned her with the boldness, freedom and discipline to excel, and to excel as a regular trait of habit. Perhaps it was here that she became accustomed to the lonely and hard-won titles of First Black. First Black Cheerleader, first and second year Black Sing Director, according to the film. Maybe she always had a peaceful relationship with her own nature, that of a trailblazer. The one who’s willing to set a few fires in order to clear the forest floor. She sees herself where no one has really seen someone like her before.

After being scouted by Willie Smith while working in the garment district in New York City, she transitioned into the world of runways. Over time, she went from model to supermodel to cultural juggernaut, seemingly knowing everyone and allowing an incalculable everyone to know and witness her. Her place at the Battle of Versailles? Ugh. I spoil nothing. You simply must go and watch the movie.

My first watch filled me with stars, the way she transitions from model to agent, and then agency owner to continued and determined table-shaker within the world of high fashion. While I so rarely have heroes, Hardison is far outside our typical Black success story. We feign surprise when Black people with a desire to change systems “from the inside out” become comfortable. They get bought out. A cool life of access quells their own fiery thirst for widespread, widely sown freedom. We yawn and change the channel. The exact opposite happens with Bethann Hardison. The world gives her more and with it, she pushes back more on the world. Thrilling to watch. I’m especially glad she told the story, rather than me finding out through various Instagram captions trending on Twitter when she dies.

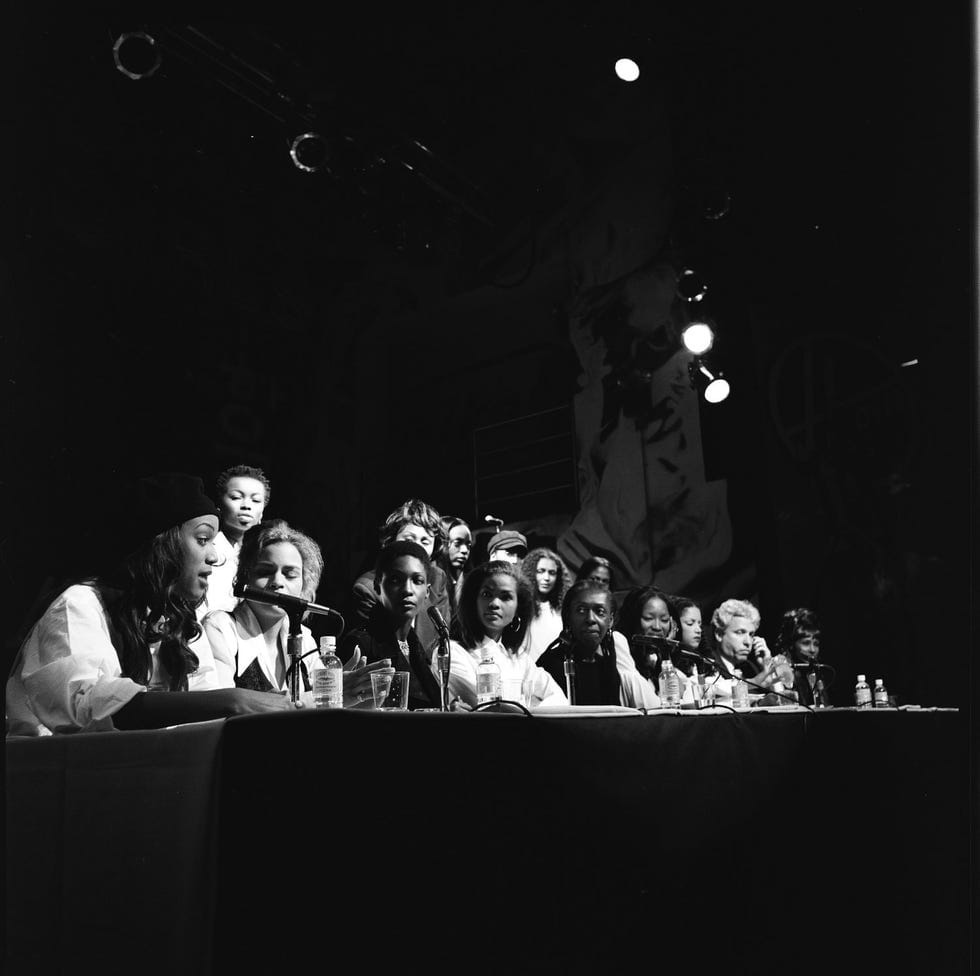

My first viewing left me considering how little I think of Black representation in media as something to strive for. Aurora James, designer and founder of the 15 % Pledge, is featured in the film stating that generational distinction.

“I mean, there’s a lot of generational differences between us. I have a lot more leeway now than she had. To some degree, like, she had to color within the lines. And now things have changed a little bit, right? … Like, representation when Bethann started was really about the runways and, you know, the magazine covers and the advertising campaigns and to me, like, if you don’t have a Black woman on your board, I better not see a Black woman on your billboard.” –Aurora James, for the documentary. Her memoir, Wildflower, is also phenomenal.

I wholeheartedly agree. It is not a true relay race if I turn around and run the same stretch my predecessor just finished. If I am to push us forward, then the race I run looks more like expanding sovereignty rather than to expand access– but that’s not to dismiss the previous work. Hardison didn’t quite know how the messaging of her advocacy work would be received, in saying “I’m not trying to help Black people, I am trying to educate white people,” since white folks are the ones in charge (and, truly, the ones actually in need of the help). Sure, now today that might be a bit cliché. And: it’s only cliché because she already did it.

I, in all my youthful glory, can make grand declarations about representation falling short only because someone called Bethann checked that box off the to-do list. She made the Black model a necessity and an expectation rather than a luxury or one happenstance occurrence. The bar of representation has been cleared, and so well that I have never once imagined what it would be like to see Black people on runways. It did not occur to me to imagine that because there was nothing to imagine; this reality already exists in my plain sight (and always has, for my lifetime). Further, we take up space in elite fashion not just because of people like her, but because of her. As she says in her own film, “There’s not gonna be another Bethann.”

To be fair, I do believe my job as a young visionary pushes our politics forward. I have been openly critical of representation politics because, as Dr. Ruha Benjamin said in her viral Spelman commencement speech, "Black faces in high places will not save us." Such critiques notch, aim and fire themselves at those who use their marginalized identities to get positions of power and then to pull the ladder up behind them. Representation in face value does not equal representation in action and policy; Black folks continue to learn this the hard way. The representation we crave are those who coalesce power and choose to become Waymaker. Here, the top layer of the unfolding sagas in this documentary makes itself plain.

Invisible Beauty told a completely different story to my mother.

We're caught up to the present day. Instead of traveling or being home in Freetown, I’m bursting into my mother's house with my laptop in my old and tattered college backpack. This time, I look less at the film (I’ve seen it twice now) and more at my mother, who reminds me of Bethann Hardison in the roles they’ve played in my life. Both have managed to tint my perceptions without my noticing, as if they filled in the color grades on the films of my life by hand as I slept. In the same way I never questioned whether I could become a supermodel due to the invisible influence of Bethann, I never wondered about the inherent nature of my own beauty because of my mother.

Gwendoline was 30 years old when she had me, her second and final birth-giving. Of the way she shaped my eyes on the world, there are none so significant as the gaze she gave me for my own body. Throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, I always considered myself peacefully, obviously beautiful. I’ve never had an "ugly phase.” I have only ever adored my skin tone (and I certainly never wished to be white). Through every stage of development, I thought surely I had to be among one of the most stunning in the world. And maybe if God continued to smile on me, I would tie for first place as Prettiest Woman Alive alongside my mum.

Of course, it remains entirely possible she had days where she did not love her body; perhaps missed what she looked like before having children or worried about weight gain. If she did, I never really heard about it. For my growing up, I recall seeing my mother every morning readying herself after bathing, adorning herself with lotion and earrings she kept in her piano-shaped jewelry box, looking at herself lovingly. To this day, I make myself late (for important appointments!) from how long I stare at my nude reflection in wonder and in glory while getting dressed. My sister and I laugh that everyone else is so lucky because they don’t need a mirror to see us.

My mother sits enthralled for the full two hours of the film showing (which is a real compliment considering her spine has so many fractures at the moment). We had to pause the film to talk. Both of us feel reminiscent of my own high school experience as we watched Bethann Hardison grow up and decide she was somebody. "There goes my baby!” my mom says, comparing us two. “Making her way and making everybody just mad.” And we laugh.

The intergenerational beauty of the film comes out when I understand just how long of a career Hardison has. My mother helps me see how significant it is for her to witness someone like this. She currently heals from multiple myeloma, a cancer of the plasma that has ushered her into early retirement. The Miss Gwen (Miss Gwen tha Baddest as I so call her) at the moment… she sits down a lot. She who is accustomed to frequent travel and hosting soirees and taking often delusional adventures, now stays home most every day, except to go to her infusions. It's a huge change for all of us.

This weekend, we’d been talking about some projects she needs to hang up for a while in order to focus on her healing. I could not understand her anxieties about working less, especially as a young person who has the next forty years of laboring to look forward to. Mummy has been working hard her whole life– I thought if there was ever a time she would relish a break, it would be now. Watching Invisible Beauty allowed her to point and say, “That! That's what I want. I don't want to just shrivel up and die."

I pause the movie and ask what she meant. "Bethann isn't dead, Mummy, I explain. “She's alive and still so active. I think she's around Grandma's age now.”

"Yes, that's what I mean." She gestures emphatically towards the screen again. "I don't want to just retire and then do nothing and then get all old and small. I want to do that. How she just lives and lives. I still have so much life left in me."

I didn't even think of that. I am twenty six years old, meaning: I am at once the oldest I have ever thought I would be and excited to get older for the first time in my life. Little Ismatu was convinced and resigned to a fate of dying young. Invisible Beauty helps me comprehend just how vast and wide a life is, and how many times you have the opportunity to make yourself new and beautiful in infinite iterations.

Watching this movie with my mum, who has said goodbye to pre-cancer Gwen and wades through this new life, helps me see the other central plot of the film: a girl who becomes a woman, who then becomes a matriarch. Bethann Hardison is the chief of her tribe and she loves us, the youth, such that she gave us the blueprints to archive her career within her life. She's a legendary fashion pillar. She could have made Invisible Beauty about the perpetually invisible Black model like she wanted to originally and left her own moving and living and knowing and growing private. She’d have every right. Even if she did want to make a record of her work, Hardison did not have to show us her fingerprints on motherhood, nor her doubts or her fears or her marriage. She could have just memorialized her CV in a documentary and left it at that. Instead, she left her blood and bones in the narrative while she is still alive. How beautiful; how brave; how boldly necessary.

Invisible Beauty allows for me and my mom to see just how many times a life can bloom for you, and how you're still human the whole way. And it gave me the opportunity be able to have the same hero as my mama, even if for only an afternoon. I always say I am in the spring of my life. Bethann Hardison tells me the secret: there are, in fact, a great many springtimes.

An open letter entitled, One Great Apology and Two Great Thanks.

Transcription below.

Miss Bethann!

Thank you for this documentary and for your upcoming memoir (I am so excited to read it). First, an apology: I'm so sorry for every time I lambasted the name of representation politics. Listen, I was not familiar with your game. I wasn’t! The hubris of youth, you know, we get here and look around and start running with how to make things better without really investigating who got us situated in the first place. I'm sorry I didn't know you until you went out of your way to make yourself known, both through the work you've done for and with others and what you do for yourself.

My first big bloom of gratitude comes from the labor of love that archival is. Thank you for making sure to archive your life while you are alive to do it. My friend Courtney Futch once said something like, “Archival is my most favorite language of love to show myself.” Ah! The peaceful beauty of being a thing worth keeping. It’s not just self-love, either. In completing and making public these records of your life, I am aware of how much you love us– those running with your baton. You said on Instagram that you are excited to share your documentary across colleges, so I know you want the youth that doesn’t go to Sundance or read Harper Bazaar to know about you. Hell yeah. I want to highlight you to my readership because the last thing that I want is for the majority of folks my age to hear about you through social media eulogies on your passing. I want to pen you my praises now while you are still alive to receive them.

Beyond the way you’ve returned me to my own brilliance, thank you for the way that you've made my mum feel. She was just glowing by the time we were done with your film. A woman who has grappled with reading difficulties her whole life watches your documentary and says, “Well, maybe I should write a book. Why not?” You cannot know what a huge deal that is! You loving on yourself in archival opens up all these ways for other people to come back to their own radiance. It is just so kind of you to prioritize projects like Invisible Beauty, particularly with such excellence. Thank you for making sure I know who you are. I bless you with my words and my actions. And I hope you see me. I'ma run one hell of a race.

May the work of your hands pass beyond you with ease.

Love,

Ismatu Gwendolyn, a young visionary

(and yes, my mama sure did name me after herself).

Jazz of the Episode:

Stepping Through The Shadow x Menahan Street Band

Tryin’ Times x Roberta Flack

Estate x Leilo Luttazzi

Slow and Easy x Speedy West

Rainy Day Lady x Menahan Street Band

Love And Peace x Quincy Jones

Share this post