an essay nearly entitled, “the orange trees teach me art-making.”

introductions

I write to you in a moment from 2024, where the sounds of the machine, business as usual, keep me up at night (words of @ivi_with_art on instagram). This loop of time, existing at once as a result of previous realities and made new in our iterations, contains human desires materialized into cascading moments of beauty juxtaposed with heinous war and death-making— and I am here, still breathing, an artist with goals of freedom. I am here to discuss what I owe to myself and what I owe to the people who make and remake me.

Of course, we have to define terms before we go anywhere. What is art? While I personally think art is defined best by its effect rather than its mere existence, I submit collected definitions across a few dictionaries to find more tangible ideas.

art (noun):

The conscious use of the imagination in the production of objects intended to be contemplated or appreciated as beautiful, as in the arrangement of forms, sounds, or words.

Skill that is attained by study, practice, or observation.

Human effort to imitate, supplement, alter, or counteract the work of nature.

A re-creation of reality according to the artist's metaphysical value judgments.

A (art-making) = B(world-making) = C (truth-telling)

In the next handful of time, I am to convince you of the following theses:

art-making is world-making (A=B), as seen in one of the above definition, the recreation of reality; the human effort to alter or counteract nature.

Art-making is divine in its ability to make and shape and reshape what we come to understand as real, relevant, true (A=C).

Truth, the ability to shape it and to market it and to have others strengthen it with their own belief, carves out reality; reality is just what we collectively agree upon; multiple realities exist at once, even from person to person.

Truth, just like any other weapon, can act as an agent of oppression or a means of liberation, depending on who crafts the narrative.

Art-making has the capacity to be revolutionary (A=which solidifies a people, which archives them, which galvanizes them to wander into greater freedoms, even if (or perhaps, especially) within their own imagination. Art (A) shapes culture (C, where culture is a collective of truths and beliefs bound together by collected, repeated actions), meaning it is one of the most powerful tools available to everyone who endeavors to create. All creation pushes on the world, which pushes back on us (A=B=C).

The primary inquiries: What is the current function of art within a capitalist society? What is the function of art in societies that propel past capitalism into new sprouts of freedom?

We also must introduce a teacher who guides my work as a whole and this particular working inquiry.

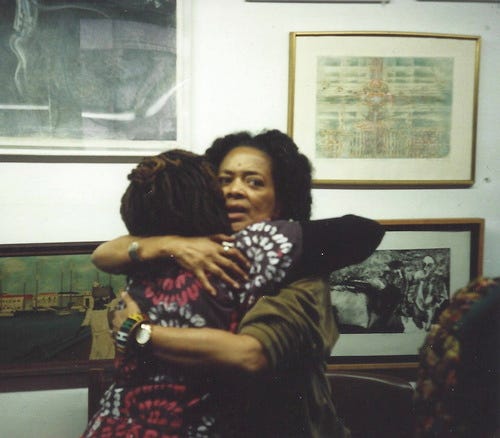

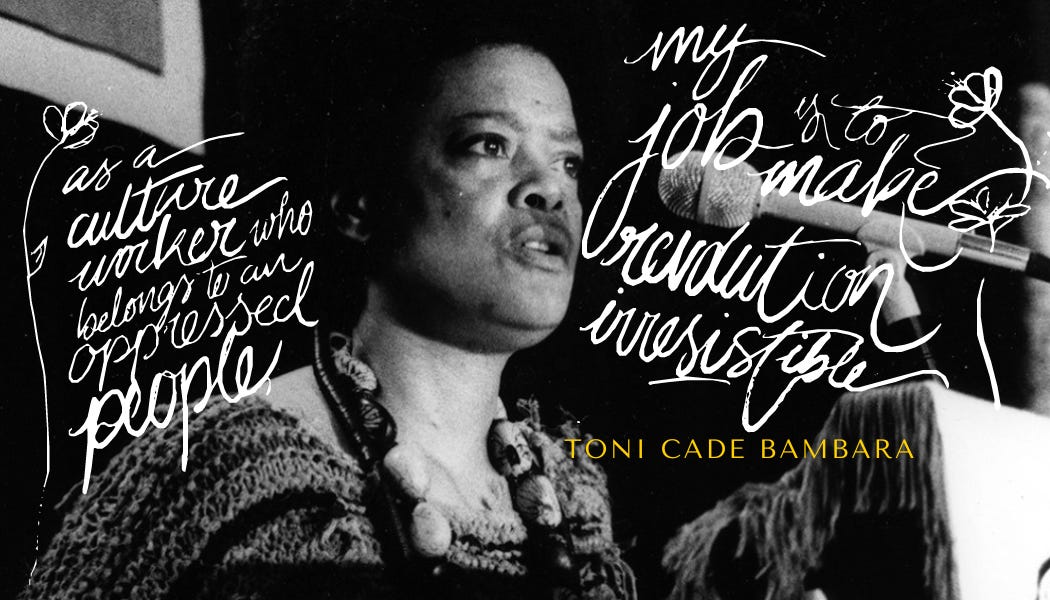

Toni Cade Bambara (TCB, pictured above holding one of her students who wrote this lovely piece about her) may be best known in contemporary culture for the maxim pictured with her above. “As a culture worker who belongs to an oppressed people, my job is to make revolution irresistible.” Filmmaker, writer, community member, Toni Cade Bambara gave life to the dance of the artist as the desire to create springing from her actions toward communal liberation. This short piece by her granddaughter? Lovely. Her dedication to being in the field— “mouth don’t win the war!”— has guided me in my pursuits of creative life, as do these moments she gave in an interview she did in 1982 with Kay Bonetti. The question: what determines your responsibility to yourself and your audience? See here two paragraphs I have previously spent a good forty five minutes unpacking.

I start with the recognition that we are at war and that war is not simply a hot debate between the capitalist camp and the socialist camp on which economic, political, social arrangement will have hegemony in the world. It's not just the battle over turf and who has the right to utilize resources for whomever's benefit. The war is also being fought over the truth. What is the truth about human nature, about the human potential? My responsibility to myself, my neighbors, my family, and the human family is to try to tell the truth. And that ain't easy.

There are so few truth speaking traditions in this society in which the myth of Western civilization has claimed the allegiance of so many. We have rarely been encouraged and equipped to appreciate the fact that the truth works, that the truth works, that it releases the spirit and that it is a joyous thing.

Toni Cade Bambara: 1983, interviewed by Claudia Tate. Answering the question, “What determines your responsibility to yourself and your audience?” All bolding my own.

This passage (along with the maxim first-quoted) guides us through this essay which stitches the following omnipresent theses into a quilt that keeps me warm at night:

(1) One of the greatest powers held in the human sovereign world is the power to create and destroy: to make, shape and reshape the world and what we know to be true. I call this world-making.

(2) We are currently at war and (I would argue) in the exposition of a new world.

(3) This world is still actively being made. What constitutes power in the hands of the masses? What methods of world-making are truly available to us?

Let’s begin.

The Madness of Opulence

opulence: noun

From The Century Dictionary: Opulence, Wealth, Riches, Affluence. All these words imply not only the possession of much property, but the possession of it under such circumstances that it can be and is enjoyed. They seem contrasted not only with theīr opposites, but with the possession of a moderate amount. Opulence is a dignified and strong word for wealth. Wealth and riches may mean the property possessed, and riches generally does mean it; the others do not. Affluence suggests the flow of wealth to one, and resulting free expenditure for objects of desire. There is little difference in the strength of the words.

The text How to Go Mad Without Losing Your Mind embraces madness from the focal point of Reason, an ideological framework codified into habits, thoughts, performances, and acceptable experiences felt and exercised by “normal” society. (For a more in-depth understanding, check this essay). What makes Reasonable thought and action within white supremacist world-making often moves in tandem step with what’s best for those same world-makers: endless expansion and endless consumption, necessarily resulting in lives of varying degrees of hell for those that deviate from the ideals of white patriarchal capitalism (read: constant exposure to premature death).

I find value in gazing at the world from my own lived and learned points of view as if I am the world-maker, as if everything gleams in Black, indigenous, poor and working class, third world, disabled, sex working glory. While I do not take stock in the idea of hierarchal truth, I ask different questions when I consider myself the authority on what constitutes sanity and rationality, such as: what sort of insanity drives a white genocidal maniac to become such a thing? Why thrust all the creative and inventive power they have access to in advancing the technologies of death? Why burn holes in the human tapestry for systems that they made up? What fuels the desire to act out of the best interest of the whole species— including, eventually, themselves and their own children? Do we ever stop to consider how buck wild that trade is— what drives a human to invent and see capital where otherwise we’re saw land, trees, seas, the beauty of being?

Enter: the madness of opulence.

Previous to the strip club, I was never compelled by the art or music of opulence.

We have come to the portion of the essay where I remind you (reader, listener, learner) that the pen who forms these studies is not invisible nor objective (insofar as one such “objective” viewpoint actually exists). My name is ismatu and I am a poet trying to convince you of something. I have (allegedly, for the purposes of storytelling), done a great many drugs. I have never, ever encountered a high like money. Not ever.

I do try and keep my recent history with sex work as common knowledge as possible (especially because it has shaped so much of my critical understandings of United States policy), yet I still find myself perpetually “coming out” with this identity. In case you’re new: I decided to become a stripper after several months of research and growing economic desperation— ‘twas very church girl shakes ass to afford graduate school city living sitcom-esque exposition. Growing up (1) impoverished and (2) of West African parentage, I was not particularly invested in hip hop as a genre or as a culture until I began dancing. The first time I entered into a strip club was also my first night working in one. All my previous hesitations about this sort of music— obsessions with money and status and drugs and hoes and the ways those things are synonymous— dissolved in a wash of mixed bills raining from the sky. The music of opulence never made more sense in my body than when I was spinning from my ankles, arms to either side of me, far from sober, flying through clouds of paper power floating leisurely. As if the money itself was happy to see me.

Currency in this society— cash, social capital, stock portfolios and assets, property, business accrual— functions as a token you trade for power. The ability and potential to make the world in your image, or, at least, your world in your image. Thus, under capitalism, the brilliance of world-making synthesizes in blue-band hundreds. Drugs are here to make you feel comfortable, euphoric, powerful; recall the claim at the top of this essay: 1) One of the greatest powers held in the human sovereign world is the power to create and destroy: to make, shape and reshape the world in what we know to be true. I call this world-making. The Anthropocene under capitalism reduces the means of world-making down to acquisition of currency; I postulate that high concentrations of world-making power without love or compassion for the human condition truly does makes one insane enough to want to harm the most vulnerable to maintain the high. It acts as a drug you never want to come down from, especially because on the comedown, you risk coming into contact with the waste produced from your consumption, from the lives you lay waste to. Money, just like other drugs, requires you get more and more just to maintain your distance from the ground.

I place my personal experiences alongside my larger inquires to help flesh out the facets of me you all have come to know. I, the pen behind this essay, was radicalized into compassion by the communities I belong to. The feedback I get of myself on the internet is mostly saintly, so I need you to understand I was so very close to committing to Black capitalism. Had I been a stripper that felt more belonging to tricks in the club than my coworkers, we likely never would have crossed paths in this internet space. I would be living a gilded life as a well-educated housewife, the epitome of Black luxury. My mother would be elated; I would be engaged in a cacophony of low to high exclusivity substances and experiences to make sure the part of me that had awoken to desires for freedom, true freedom, stayed sleeping.

Opulence: that fragrance that blooms off the wealthy, not just having a lot but having far, far more than most— acts like a drug. In this iteration of world-making, a life of luxury denotes the ability to consume endlessly and produce endless waste without consequence or delay. The intoxication of power lulls you into forgetting your place on the human tapestry— not as the king, nor the sole weaver, but one stitch among billions. That’s the thing about drugs— they numb the pain. They fill you with a false sense of power and euphoria. The opulence gets you so high that you look down on anyone not managing to soar to your level. They must want to be down there, broke, starving; it’s all a mindset. They must not quite… deserve it like I deserve it. Take another hit. Take another hit. The wealthy find new ways to bloom, they take another hit, another party, another award show, another private yacht/jet/island and we, the masses left down here to rot amongst their ruins, wanting so desperately to escape the hellscapes made for us, gaze upwards and long to be up there, glittering, with far better drugs.

world-making shapes truth.

The art that comes from the elite triggers disassociation by design— art-making is worldmaking. The power they wield cannot spring spontaneously from thin air; just like energy, I argue that power cannot be created nor destroyed, only transferred. Our ruling classes benefits from us considering this world bereft, beyond saving, because it keeps us looking up, gazing at them, longing for escape— which, in turn, keeps them powerful enough to continue floating up there, aspirational, away from the worlds they destroy in the wakes of their creations. Your attention is deeply lucrative. Clock the positive feedback loop: they continue to create a world that blooms endlessly for them while we stand mystified, tricked into understanding the power of world-making exclusively as capital. In such a world, the only way to escape the horrors of capitalism is to cause them to happen to someone else.

Music and visuals and dance and literature, all sorts of art, become escapist as a means of reinforcing the status quo and, in fact, mimic the drugged life of opulence they (our most endowed world-makers) indulge in. Art-making is a display and an execution of power; it’s not just about telling the truth, or a truth, it’s about shaping truth itself. Art-making is truth-telling.

Social media is my favorite truth-shaping, world-making drug.

I’ve written about this before, how life in imperial cores (like the United States, where I was born) necessitates that we have drugs of comfort and numbness everywhere to disassociate from what we cause. As easy as it is to focus on the the 1% that holds the majority of the world’s wealth, my countrymen in Sierra Leone spend their lives gazing up at what they imagine the United States to be like at any level of living. I grew up in poverty there, in various states in the US. Yes, there are those glittering above me; that’s not to say I too do not float above the decay of the colonized world, or that I haven’t managed to over time. By the time I was a teenager, I was navigating food insecurity in a (relatively) stable home in the suburbs. That came with its own challenges; that’s stratospheres above food insecurity in a rural part of Sierra Leone.

Socials have changed our methods, our lenses, of understanding the world around us, which, in turn, reshapes the world. We can see that clearly with the ongoing genocide in Gaza, which likely would have gone completely unchecked if Palestinians weren’t able to live-stream their own deaths to the connected world, crowdsource funds to evacuate, and call for action. Iraqis had no such media to commandeer in 2003 when the United States fabricated the War on Terror and they were slaughtered for years. 500,000 estimated dead by the will of the empire. Mass graves we are still finding. For oil.

Remember: no tool we have widespread access to exists without the consent of the empire. I don’t care how radical it feels; if they allow it to exist, it’s because they have made carefully calculated risk assessments. In the same way social media works to reshape reality, the wide spread circulation of graphic scenes and rising death tolls work to numb you to the atrocities of life. It’s the same eerie feeling I witnessed during the explosion of Black Lives Matter uprisings across the world: more visibility does not always equal more sustained action. Jasmine on TikTok said it so well.

Transcript from video: when we take shrooms, we experience an emotional peak: you go from here to here to here. When you smoke weed, depending on the strain, either you experience a burst of creativity, you experience some sort of euphoric sedation, or you experience a heightened sense of paranoia and anxiety. When you watch TikTok first thing in the morning, you might watch a video of a baby laughing, the next thing is a white cop playing basketball with black kids in the middle of the street, the next video is a white cop holding a black man at gunpoint for a simple traffic stop, the next video after that is TikTok Shop tryna sell you the spin brush…you’re going to see content that takes you [up] here, [down] here, [up] here, [down] here. When you watch the news, what do they do? They give you heavy content, light content, heavy content, light content, cause if they only give you one or the other you won’t watch it. You will not engage.

Art-making is world-making: the art of marketability and riding waves of virality across the world, the art of journalism and video sharing, the art of connection across timelines and oceans, poets and illustrators and photographers sharing pieces that stick on me so intimately they move flesh and bone out the way to imprint my heart. Those things coexist next to the wills of the empire. We have social media because the world-makers in charge (again, white genocidal war-mongering maniacs) can at least attempt to degrade our sense of horror and urgency with shock value and overexposure. It normalizes something that was once unthinkable, seeing the same scenes of subjugation over and over again. When I had a Facebook in 2012, images of nudity and violence never, ever would have proliferated like this. We must never fail to ask why. What important truth is being formed here?

Let’s return to Toni Cade Bambara’s, “my job is to make revolution irresistible.” Lesser known is the morsel she said just before defining her job as one artist belonging to oppressed people, in answer to the question “what is the task of the artist?”

The task of the artist is determined always by the status and process and agenda of the community that it already serves. If you’re an artist who identities with, who springs from, who is served by or drafted by a bourgeois capitalist class, then that’s the kind of writing you do. Your job is to maintain a status quo, to celebrate exploitation or to guise in some lovely, romantic way. That’s your job.

Then and only then does she follow with the famous maxim: my role as a culture worker belonging to oppressed people is to make revolution irresistible. But that certainly is not every artist’s job. There are a good many powerful, world-making artists that maintain a status quo, that romanticize exploitation. They play on the radio and star in feature films year after year after year.

I just updated my thoughts about Beyoncé and went viral (again) for dissenting to the airs of working class solidarity she dawns when it’s time to circulate her wildly lucrative art. While she certainly is not the only example, it does pain me particularly that the reigning monarch of the music industry chooses liberation in her works and capitalistic oppression in her business decisions. As previously stated, money is a blank-check for world-making.

There are many ways to make and shape a world outside of money— art-making is one particularly powerful tool as it allows us to expand (or confine) our imaginations to what is possible. In consuming art, the feasible solidifies. The dreamscape takes shape, registers feeling in our bodies. Art reflects back to us the lens of the artist, what they yearn for, what they know to be true, and shapes our world-view accordingly. Art-making is world-making— the two are not just synonymous, they are the same. We in the working classes, the survival classes, often think art-making is only for the rich or those with leisure time, that it’s unrealistic, that art is a luxury compelling us to disengage with our material tasks (and that disengaging from our material tasks is a bad thing). Who benefits from those beliefs? What if we were to make or engage with art that compels us towards our circumstance? What happens when art exalts the common thread, when art takes our upward gaze and turns us towards one another?

We crave truths that feel usable to us.

I saw a video commenting on how fracturing it is to navigate a reality that art does not reflect the times, stating “they was not singing about brown booties and coochies while we was protestin’ in the streets!” These sentiments stitched by a creator I love [@(hereciasmansion)] saying, actually, escapism really does reflect the time.

“I don’t think that this is true it all. And just because we don’t think it doesn’t reflect the part of the times that it should, doesn’t mean it isn’t reflecting any of ‘em. If you just scroll TikTok at any given time, in any algorithm— you will see very quickly that there are many people who are intentionally, blissfully unaware of, you know, the more serious things going on in the world, and I think that music 100% reflects that as it is currently in the mainstream.” —Herecia Grace, February of 2024

Celebrity requires aspiration to maintain the hierarchy and enough relatability such that we see themselves in us and don’t wish to seize back the power they siphon. This often results in artistic powerhouses dressing their works in bite-sized pieces of revolution… which, to me, is insidious. Absolutely nasty work. The art does absolutely reflect the times: it tells truths most beneficial for those in charge of current world-making.

I think what we’re craving is usable truths for us, a lovely understanding of art further expanded upon by Toni Cade Bambara:

I want to lift up some usable truths. I want to lift up some usable truths, like the fact that the simple act of cornrowing one's hair is radical in a society that defines beauty as blonde tresses blowing in the wind, that staying centered in the best of one's own cultural tradition is hip, is sane, is perfectly fine despite all the claims to universality through Anglo-Saxonizing and other madnesses. —TCB, 1983

We know the truth of how much we need a world that belongs to the masses again, rather than be domesticated pets inside our own cubicles. Mules of the ruling class, we plow their fields and run their generators and we are desperate for heroes— so much so that we lift up those who make themselves enemies of us because they give us just enough truth to feel something. And it is so difficult to feel anything when you are drugged out all the time. Most of the art around us builds a world that detaches us from our usable truths.

At least, the art of the western world does.

What of art that liberates?

Remember what we began with: I start with the recognition that we are at war.

If art-making is world-making, and world-making is essential to liberation[link essay]: what is the world we would rather be living in? How do we then march toward that instead of a away from something?

In the United States, the war being fought is through information. It is not profitable for the core of the empire, the supposed envy of the world to have bullets raining down on their civilians all the time. So they subdue us through the truths they tell, and the truths that allow to be told. They make war on us via their policies (remember: poverty is a policy choice, not an inevitable circumstance of humanity). And, as a whole, this is war that hides itself in plain sight. Our attention spans are shortened so that we are blanked with atrocities followed by puppies to keep even our means of information-sharing a drug.

Sudan has had a thrilling recent history of overt war: the people won their popular revolution in 2019. They won. That is actually the backdrop for the current war of attrition occurring now, where two military groups kill each other with as many civilian casualties and atrocities as possible to make them easier to control when gaining power [pause: that linked article by Yassmin Abdel-Magied and Alaa Satir is superb. It is the best breakdown of the current war I have read synthesized to date. Please read it]. In Sudan’s popular uprisings, the artist is in the unique position of truth-telling. From the photography ingenuity hallmarked by Rashid Mahdi and the current renaissance of art aided by the internet mirror each other in how much they resonate with the people rather than the wills of dictators. Art that reflected Sudan back to herself led her to her own freedom.

I read an excellent (!!! excellent) article by Dr. Bedour Alagraa, Sudanese professor and “wayward political theorist” about the pendulum swing of Black Liberation, which looked at the 2019 successes in Sudan.

One thing that I wrote in last year’s piece, was that the uprisings in Sudan led to an explosion of public art. All movements— big and small— are accompanied and sustained by expressive and artistic mediums, which are the most significant ways we transmit and tell different stories about who are as Black people, as [Sylvia] Wynter reminds us.

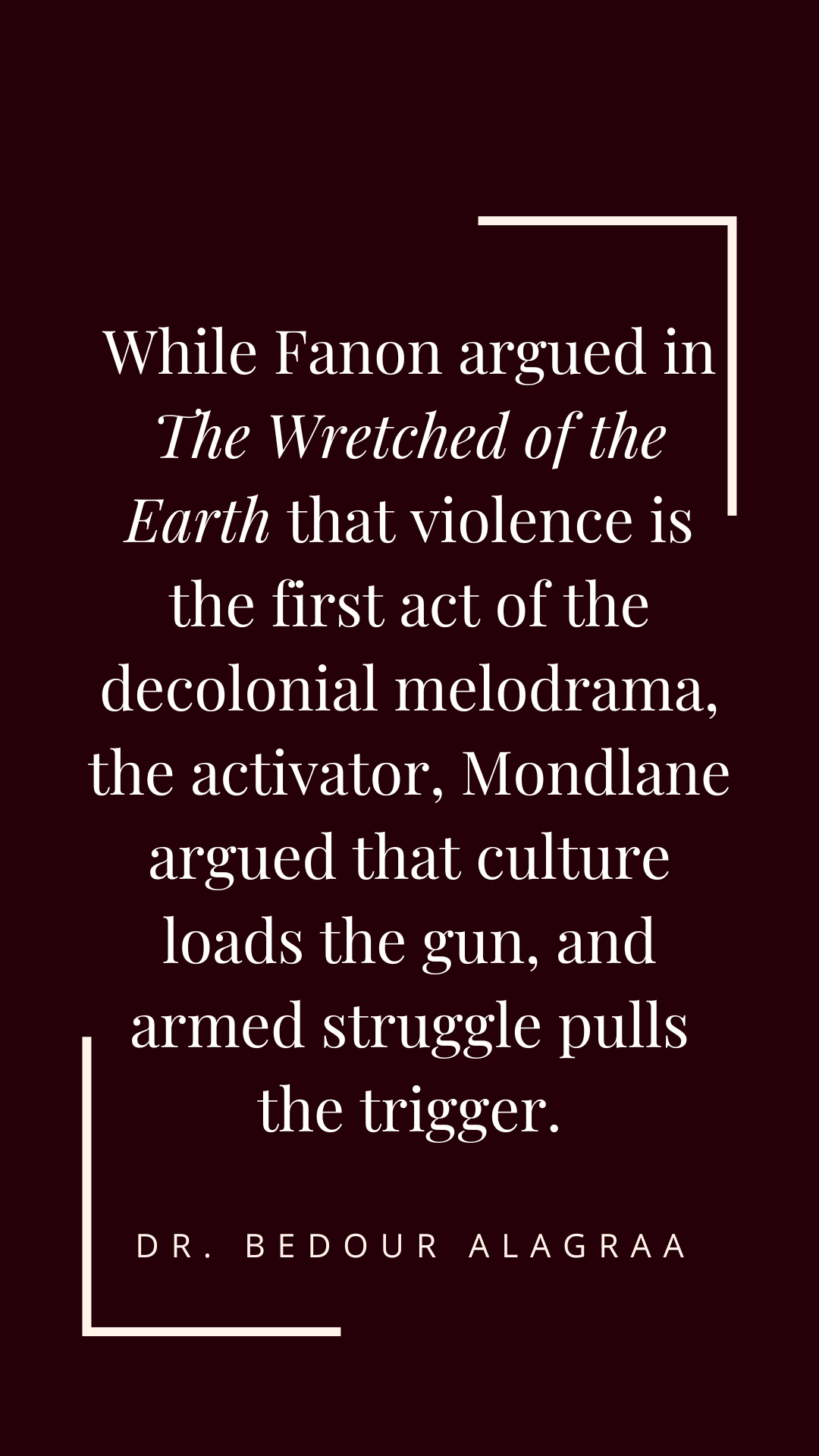

The pendulum swings towards repression, and the weight that swings it back cannot be credited to national parties or revolutionary armies. It comes from music, poetry, dance— what Woods’ referred to as “cultural productions of Black working-class organic intellectuals.” Take, for example, Eduardo Modlane, founder of FRELIMO, which sustained a 10-year war of independence against Portuguese colonialism. In his book The Struggle for Mozambique he argues that the earliest signs of resistance were not in the factories or in the barracks, but found in the traditional songs of the Chope people of southern Mozambique. He argues further that revolutionary and national consciousness was sown first in the traditions of the Chope— including folk songs and poetry— followed by intellectuals, artists, painters, undoing the attachments to vanguard is that has since long dominated Marxian thinking. The final stage— not the first!— of political consciousness was that of industrial workers and political organization. While [Frantz] Fanon argued in Wretched of the Earth that violence is the first act of decolonial melodrama, the activator, Mondlane argued that culture loads the gun, and armed struggle pulls the trigger. Revolution is, directly translated, about returns. Culture— blues, poetry, storytelling, offers, as Suzanne Césaire wrote, a return to ourselves. The pendulum swings away from liberation, and we must swing it back.

Art-making: not as a leisure activity, solely or simply an expression of self, but as the most important medium that we have to communicate. Art-making which hides the seeds of how to be a human stitch in the tapestry again, passed for safe-keeping in the hands of our indigenous. Art-making as a means to mobilize the weapon. If armed struggle is the first action of finding a world beyond colonization, beyond what we can see, culture loads the gun. The role of the artist is to load the gun.

What are our usable truths? the truths we might use to swing the pendulum? the truths which orient ourselves to believe in our agency more than we believe in the inevitability of suffering death? why do we believe that it is okay for art to sell us narratives of gods among men? why do we think we cannot ask or expect anything of our culture-makers? why are we convinced we have to suffer?

what are we fighting for? what do we dream of?

what do I dream of? art like the orange trees.

the divinity* of creation,

*where divinity is freedom.

This essay did not come to me until I asked my elders for help. I’m far from New York, and my mother moves through cancer with my father at her side, so I petitioned the orange trees in my parent’s backyard.

how do you make art?

They said, to my understanding:

Seamless art passes seeds beautifully. curated creation which slides in and out of our mental spheres, more powerful and more porous than we want to believe— and that’s true for both mind and art: the bloom, the fruit, and the harvest. the allotment of trust when my buds and flesh pass through you— intimate, right?— the feeling of loss of something no longer being expressly mine ; the great relief, the reverence, the pride at watching my seeds grow outside me. savor this moment we share in time space. taste these words with me. tell me they’re not pressed up against your skin.

I eat an orange and consider: there is no way to consume the art of the orange tree without it, however temporarily, becoming a part of me.

conclusions

the orange trees in my family’s hard sun bloom with no sense of ownership over their art form; no sense of obligation to our faculties or property lines. collectively, they shift the air of entire streets. the air weightier, cooler, laden with orange blossom. evidence, in and of itself, of the world they build with their art. the bees in bliss. their weighty fruits change things.

dead and decaying fruit dissolve into the earth in peace. we could live in a world where we do not fear death; we could live in a world where death, no longer weaponized against us, makes the ground fertile for life again. in this world’s cruelty, in all of the creative force we produce contributing to the war-machines, we have forgotten that death is sweet.

freedom where world-making and sovereignty is not to make oneself a God among men, but to see, allow, and uphold divinity in each and every man. Creation is an extension of the divine, where divinity is freedom. I was made in the image of God so I seek to be free, with everything.

what do we owe one another?

the art that we often create and eat in the anthropocene tries and fails to emulate the fruit tree. all world making is an act of divinity. made in breath the creator’s sigh such that we, to, are able to create. as far as the flower knows, the whole world is leaves and bees and the life tree. every act of creation is world-making. such is love: the purest pleasure of unmitigated life. I ask her, the tree, her motivation. she beams a child from the sky. An orange, ripe, thunks at my feet.

Every son has a becoming.

The day the war planes are quiet I will bloom art benevolent and sweet, like the orange trees. What of today?

what do i (ismatu, an artist, a sun becoming) owe to this world I am stitched into?

I am an artist belonging to oppressed peoples, among them the rural, the Sierra Leonean, and the disabled. I give my first fruits over to my beloveds. I present to you a project I’ve been working on with Social Income for over a calendar year now.

I believe we need a quick reintroduction to the author of this essay; it’s been a second since I laid out my history.

My name is Ismatu and will see a free and fed Sierra Leone in my lifetime.

I consider it my responsibility to use my education (bachelors in Creative Writing and Global Health Studies, master’s in Clinical Social Work with a concentration in Health Administration and Policy) in service to my communities— my rural, indigenous, diasporatic, disabled, stigmatized communities across Black US America and Sierra Leone. I first began my research on Ebola in Sierra Leone six years ago. I was nineteen and optimistic about our future. I am now twenty five, a tinge more studied, radicalized into bypassing academia and sharing my findings directly with the public. I believe the Sierra Leone Association of Ebola Survivors, SLAES, have many lessons in their organizing for their continued livlihoods, especially for those of us in the North/West still battling COVID-19 as an invisible-izsed killer. Alongside other initiatives, I am campaigning $200,000 USD to pilot a Universal Basic Income program for the entire Kenema chapter of survivors, the first such program in Sierra Leone’s history. For this, I am proud to partner with Social Income, a non-governmental organization based in Switzerland that runs entirely on a volunteer basis and enacts a “no fees” policy— meaning every single penny donated will end up in the hands of a Sierra Leonean Ebola Survivor.

This is our second big project of the Revolutionary Healers series, which I aim to become. Over the next month, to raise awareness, dollars, and mobilization, I explore the following theses, consistent with the findings of my research:

Poverty is both a policy choice and always the backdrop for war.

Unchecked spread of disease leaves infrastructure prone to collapse. Stigma is the enemy of progress.

Stigma comes from believing other humans are not and cannot be like you. There is no exceptionalism across the Anthropocene; if it is happening to them, it has already happened or is already happening to you. This especially the case with disability: You are either disabled today or disabled tomorrow.

There are a great many tactics of war, making it more common than we think. Those of us in the United States and other Western strongholds navigate a war in plain sight.

Grief and memorialization is necessary for a populace to mobilize for their best world.

A world that belongs to us hinges on how quickly we can come to believe, in mass, that we can care for one another.

This is my first iteration of life’s work blooming for you, for the good of my most beloved communities. I so elated to see this day. Thank you God.

I hope the work of your day plants hope for your blooms tomorrow.

Or, simpler said,

Peace.

ismatu g.

the role of the artist is to load the gun.