introduction:

We begin with a morsel from Toni Morrison, great Black American author:

The point is so that it doesn't look like it's sweating, like that effort, you see? It must appear effortless! No matter what the style, it must have that. I mean, the seams can't show.

—Toni Morrison, interviewed by Jane Bakerman for Black American Literature Forum’s Summer 1978 issue

Consider first this over-arching thesis: the brilliance of educational work lies in the exact opposite task. Where most art forms do work, significant work, to make it look easy (see: the seamless novel, the floating ballerina, the effortless jazz player plucking a new melody from the ether), the teacher seeks to stop a moment in time. Did you catch that? See the mechanism? The split-second decision? Look closely. Don’t miss it. Taking the form, shaking it off the model, turning her technique inside out, pointing at the seams, the intestines, the world-making in each intrepid and intentional detail— did you miss it?— we find the task of the Teacher, an occupation I prayed with every Reasonable and self-perseverant burst of blood I had to never become.

why are we here?

Threadings. is a newsletter and podcast in which I explore the interconnectedness of our worlds and freedoms. Exploration tethers me to the art of world-making. In examining the seams which bind my life and politic together, I stitch for you all a patchwork quilt: my revelations on the systems of this world, the odd and beautiful realities of existing in public, the ways I am ignited and ionic. A seamstress of thought, just like my mother(’s mother’s mother)— here I am, hunched over my keyboard sewing machine, all in a labor of love.

I write to you today because I have apparently made it look easy. There’s a cadence on the internet that occurs without fail: I state the need to read while giving you a piece of myself stitched together » someone (many someones) respond with the idea that I “must not know what it is like to struggle to read.” Kindly: this infuriates me. Not just because of my pride (why do people assume instead of ask?) but because it’s cheap analysis. The better question is:

Why do I, among so many, have a knee-jerk reaction of doubt, disbelief, and anger when someone asks me to read?

I announce myself as the narrator as I compete with for your attention for the next… forty minutes or so. Hello, my name is ismatu; I am a poet; I am writing a persuasive essay. I am doing you a favor announcing these things to you rather than silently wiggling into your brain to change your mind and have you think it was your idea. I encourage you to consider me critically.

This newsletter-podcast is called threadings. because I want my seams out and obvious. Here, I can show my work; display for you the sewing pattern; have you trace with me the stitches that assemble me into an artist, a teacher, a great big worm tucked in a fancy scarf. I am here to be educative. I want you to remember that I am a person with very specific lenses on the world. I want you to remember that everything about our current existence in the Anthropocene (as in, a human-sovereign world) is by intentional and by design. The Anthropocene is intentional and by design. Someone(s) made all this up. World-making is an intentional and detail-oriented process; what can be made can be remade, over and over again. I want you to leave this space having exercized you ability to loacte the seams. Leave this place looking for the threads of this world around us.

We have four central theses interwoven throughout the essay. Challenge yourself to find them in the supporting arguments, even when I don’t state them explicitly.

(1) the ruling class benefits from illiteracy.

(2) short-form video entertains more than it sticks.

(3) reading is a discipline distinct from listening, watching, or other forms of literacy. It’s a skill that needs to be honed separately.

(4) Absolutely no one comes to save us but us.

And we’re off!

The reason you hate reading is because the ruling class benefits from illiteracy.

Not total illiteracy, mind you. That’s bad for business. The ruling class (law and policy makers, oligarch businessmen, celebrity, hedge fund managers buying up single-family housing, etc.) want you literate enough to be able to work for them, but not so literate that you realize how badly the working class gets fucked over in this world-making. Read enough to be able to consume and to execute, not to consider critically, certainly not enough to create. Because then what? A mass of people realizing we can create and recreate everything we see and touch to something kinder for us?

Ghastly. Absolutely

Countless journalism, podcast projects, quantitative and qualitative research death knell the same morbid conclusion: the US-American populace cannot read1. I’ve linked a brilliant podcast project below, it’s recommended all the time— Sold a Story. We know! We know that illiteracy— the inability to read, or the inability to read well enough to have it serve you— we know it’s a massive problem. An epidemic of sorts. We’re simply too exhausted to care.

I’m not spending time analyzing data here. Others have already done it— for my purposes, it’s kinda useless— not that data analysis is useless, but that . Why?

(I’m saying this as a trained therapist, okay? Deep breath.)

Your relationship with reading is more than likely a direct result of your experiences with authority figures as a child.

In a great many iterations. If you were lauded for reading, put on a pedestal in front of your peership, it might be stress-inducing to return to work the muscles you know have atrophied. Are you still good or worthy of help if you cannot read voraciously, like you did as a child? If you were labeled a problem, difficult in class, slow… I bless and keep you. Worse, if you were made to feel less than because of your reading ability (unintelligent. burdensome. a waste of space. bound for prison) then you likely have a literal stress-response when someone mentions or suggests reading to you. Reading is a site of trauma your body holds onto for most of us. Anyone that suggests reading must not understand what you went through. Every objection imaginable will materialize when someone suggests that you try to read.

This is why I think the data here is irrelevant to spurring anyone to real action. You can’t just brute force your way through a trauma response.

Many of us were given reading as homework exclusively— never as a fun or revolutionary tool, a tool of imagination— so it often feels like drudgery, even still. None of us have a neutral experience with the discipline of reading and that is by design. We live in a world ran and ruled by the written word. Similar to money, right? The tool itself is not necessarily bad. However, in this iteration of world-making, proper literacy in reading and writing (as well as financial literacy) are often the difference between agency, freedom-seeking, and autonomy for self-determination and working in someone else’s world-making in abysmal conditions perpetually. Which means:

If the empire wanted you to have a good relationship with reading, they would ensure one.

Just look at Cuba, beating our US adult literacy rates despite decades of overt economic warfare. Your relationship with reading is fucked up because burning books is a bad look. The empire utilizes overt, violent oppression like that as a last resort, because it makes it near impossible to seamlessly convince people they are not oppressed. And to hide an empire like this? Of this size? People need to not know.

Editor’s note: where else is the empire seamless in their oppression? Look for those threads everywhere.

The far easier route: traumatize the kids. Make them hate reading. Tie plenty of guilt, shame, and fear in the process of returning to reading in adulthood. Make them feel like it’s an innate talent— you have it or you don’t— rather than a skill you need to learn, hone, and practice. You never have to burn the books if no one ever wants to read them in the first place. And this means you can allow texts that chronicle blueprints for our collective liberation to hang out in plain sight. The internet age is the most collective access to information we have ever had as humans in every iteration of our timeline— and most of us cannot read it well enough to allow it to change our lives.

I could spend this section pulling numbers and analyzing data, but I don’t think that would change much. We know it’s a problem— we exist in and under the consequences. Instead, I want to tell you instead about my life.

why does the narrator, ismatu gwendolyn, like reading?

I was an avid reader as a child as a means of escapism because home was spooky. So I didn’t like reading, I liked not feeling what was happening around me. Reading had the same allure as TV or video games YouTube videos (but I experienced childhood in a time where TV didn’t work if it was raining or snowing and YouTube videos took thirty minutes to load a piece). Non-fiction words felt like homework in childhood— honestly, without understanding the importance of studying the human tapestry as this big, long, interconnected story, non-fiction still feels like homework to me.

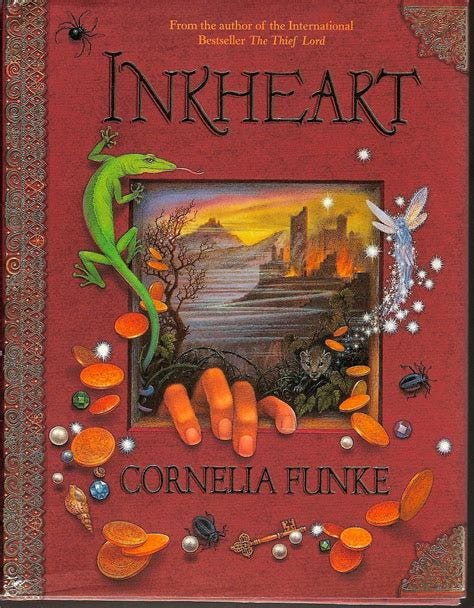

Reading fiction as a child opened up three very important conclusions: (1) that reading could feel good, (2) that other worlds were possible, and that (3) it was possible to make up worlds. I remember the book that unlocked that third conclusion: Inkheart by Cornelia Funke. Someone just… made up the world cast between the pages of this book. Multiple worlds, in fact. What does that mean for this world? How much of my world can I make up?

Listen: the best gig in the world is to be a little black girlchild that reads. Everyone is rooting for you all the time and everyone leaves you alone! Nobody asks you no questions. No one bothers you with a book in your hand. This was (and is) a great relief to me— even as a bitty little being I was trapped in the body of a girlchild, which means that people always expected me to be socially graceful and kind and extroverted (of which I was none).

Another editor’s note: Literacy is just your ability to use a tool fluidly. Wherever there is a human skill, there is literacy: data literacy, social literacy, ecological literacy. I consistently find my generation (Gen-Z) to be high in media literacy and low on aural and written literacy. This essay focuses on literacy within the written word with this in mind. Take a breath.

The reason I champion reading is because I am from peoples who cannot read easily.

I did not come to reading consistently because the act in itself was easy. I have multiple learning divergences— dyslexia, autism, ADHD. I still (still!) struggle to focus my mind on the page, and at this point I read for a living. I came to reading because not reading was worse. Not reading meant someone tried impose the role of a girlchild onto me: to rope me into chores, or force me to talk to them, or otherwise engage in ways that felt foreign to me and my body. I didn’t know how to answer the questions of my constant discomforts— why words swam on a page, why I couldn’t move my body in certain ways, why I had to look people in the eyes and speak to them on demand— until early adulthood. I just knew then that reading was safer than pretty much anything else I managed to do poorly.

I also advocate heavily for written-word literacy because I know the reality of illiteracy. My mother spent her life being told she was too unintelligent to realy make something of herself. She—brilliant seamstress, prolific orator, hostess, event organizer, master chef (as in fed a wedding of 300 several courses with herself and two of her friends, master chef)— stopped being able to help me with my homework once I reached the fourth grade in the United States. She knows her letters, so she is not completely illiterate. She is not fluently literate (as in, she has too little practice with the tool of the written word to have it under her full command). I inherited my dyslexia from her. Nobody thought to check for learning disabilities or alternative modes of learning in newly independent Sierra Leone. They just thought— or it was just easier to believe— she was “slow.”

My father is from the only tribe indigenous to Sierra Leone. He is an anomaly because he got to pursue his associates degree in the United States. He was a reading fool. Uncommon for his area: he comes from upline Sierra Leone, what we would call… I don’t know… back-country in English. It’s essentially untouched jungle. Most of my paternal family is not written-word literate, functionally or in any sense. Which meant: my parents would buy me a book sooner than they bought us groceries, if it came down to it. The knowledge that the difference between us living in the United States and Sierra Leone during the heights of the war hinged on the fact that my father could read well, used literacy to be able speak well, and got opportunities to study here? It changed us. Reading held the difference between chances at generational safety and chances of losing your kids in a war.

In college—

Editor’s note: we’re skipping a lot about the narrative of my life. This essay went from poor kid in unstable home environment to college student. While I don’t feel the need to fill in all those dots, imagine me sliding you a paint by numbers, okay? Note to yourself how unusual it is to be a kid with multiple learning disabilities, whose primary caretaker could not read a chapter book comfortably, ending up on full-scholarship at a collegiate institution in the United States. Especially not a Black kid. That’s word to Miss Gwen, because I’m a public scholar and my sister completes her phD in fucking music theory in a handful of years. Pour some respect on my namesake. Anyways.

In college, I studied oral history and traditions of record-keeping regarding Ebola in Sierra Leone— specifically an oral history project because many of the survivors cannot write in any of the languages they speak. They would sign consent forms with their fingerprint; they could not spell their own names. This leaves them vulnerable to being exploited by foreign researchers, who come to study the long-term effects of a disabling virus, make money of their bodies and stories and personhood, and leave them where they found them. They don’t have access to the research because most of them cannot read what’s been written about them.

I chose to fashion my research in this way to honor stories that would otherwise never be able to be told, because the researchers that came before me only spoke in English and mandated literacy to be able to consent to the study. Sierra Leone has such poor literacy in adults because public education was systematically defunded and privatized until the conditions were so desperate and volatile that civil war took root— now, every school in Sierra Leone requires fees from parents to attend. I champion literacy because we are on a similar road in the United States.

And this is just as an aside: I don't tout Sierra Leone's history as a “cautionary tale.” It is what happens to nation states when you systematically deprive people of their ability to seek and architect their own happiness. When you wage war on the people via economics, when you wage war on the people via drugs, when you wage war on the people via imprinting them with ignorance that they did nothing to deserve but suffer under? Physical, violent, gun and ammunition war follows. It's the only thing that can happen next. Sierra Leone is not a cautionary tale. The same road, we're on the same road in the United States.

As an adult, especially as an adult that has had Covid, I read and write every day because I have a brain that disintegrates this particular skill faster than many of my counterparts. I have learned the skills of social grace, and public speaking, and data analysis by similar necessities, and I’m required to use these skills on a regular basis, so they stay sharp. Reading and writing are disciplines I have to choose to sharpen actively, because if I don’t read, then I won’t. I don’t have to read if I don’t want to. I am a gifted and prolific speaker— inherited from both my parents. I began public speaking when I was fourteen. I don’t have to read to garner and keep an audience. Many (most!) popular public figures do just be talkin! Not a source in sight! I read and write because it keeps me responsible to my constituency (which is you all).

This is another reason reading, as opposed to watching a video or listening to a podcast, is a skill worth developing on your own— to protect yourself from adopting the feelings of the narrator (me, ismatu, a poet who is trying desperately to convince you of something).

Words from Toni Cade Bambara, great Black American artist who manages to know me before I was born, discussing why she writes:

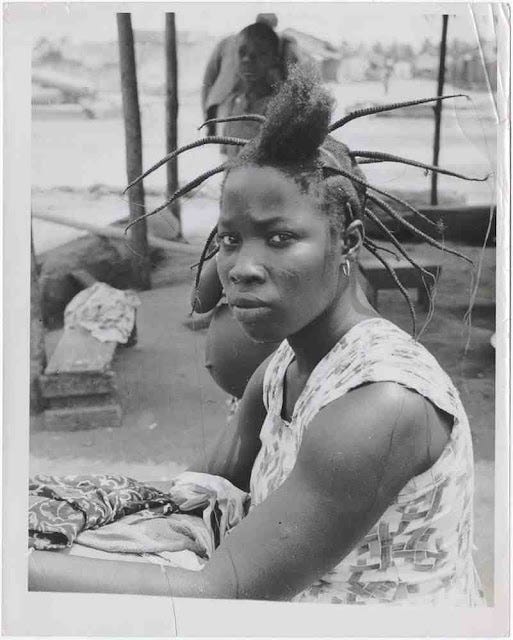

I do not think literature is the primary instrument for social transformation, but I do think it has its potency. So I work to tell the truth about people’s lives; I work to celebrate struggle, to applaud the tradition of struggle in our community… like the fact that the simple act of cornrowing one’s hair is radical in a society that defines beauty as blonde tresses blowing in the wind;

…

It would be dishonest, though, to end my comments there. First and foremost, I write for myself. Writing has been for a long time my major tool for self-instruction and self-development. I try to stay honest through pencil and paper. I run off at the mouth a lot. I’ve a penchant for flambyoant perforance. I exaggerate to the point of hysteria. I cannot always be trusted with my mouth open. But when I sit down with the notebooks, I am absolutely serious about what I see, sense, know. I write for the same reason I keep track of my dreams, for the same reason I meditate and practice being still— to stay in touch with me and not let too much slip by me. We’re about building a nation; the inner nation needs building, too.

…

I began writing in a serious way… when I got into teaching. It was a way to keep track of myself, to monitor myself. I’m a very seductive teacher, persuasive, infectious, overwhelming, irresistible. I worked hard in the classroom to teach students to critique me constantly, to protect themselves from my nonsense; but let’s face it, the teacher-student relationship we’ve been trained with is very colonial in nature. It’s fraught with dangers. The power given to teachers over students’ minds, students’ spirits, students’ development— my God! To rise above that, to insist of myself and of them that we refashion that relationship along progressive lines demanded a great deal of courage, imagination, energy, and will. Writing was a way to “hear” myself, check myself. Writing was/is an act of discovery.”

excerpts from Conversations with Toni Cade Bambara, emphasis and bolding my own. TCB responds to the question, “What determines your responsibility to yourself and your audience?” posed in an interview by Claudia Tate, 1983

Recall what I, the narrator and invisible pen, said to you at the beginning of this essay: I am here to show my work. I am in the business of revolution, page by page, meal by meal, moment by moment. The world I wish to see has seas of makers, millions and billions of distinct fingerprints all over a brand new mode of being, which means learning. Which means teaching. Teaching has made me very serious about my pen, because I too run off at the seams. I want to make sure I show you my work. Writing is what keeps me tethered to worlds I don’t yet know (what you don’t know will make worlds).

Let’s zoom in on that tidbit about teaching and accountability. There’s a drop of that last paragraph I left out.

“I frequently discovered that I was dangerous, a menace, virtually unfit to move the students and myself into certain waters. I would have to go into the classroom and beat them up for not taking me to the wall, for succumbing to mere charm and flesh, when they should have been challenging me, “kicking my ass.”

ah.

You all take my word for it WAY too much for my liking! I am able to inject emotion into you from video with a sickening ease. Reading what I write, sans my beautiful speaking voice and pretty face, gives you a moment to taste the words in your mouth to see if you ACTUALLY agree.

This is not to say emotions do not contribute to our sense of knowing. I did a whole talk with Boston Ujima where we as a thinking community highlight our bodies and emotions as important sites of knowledge. I am saying here: social media television is designed to embue you with emotion. You are supposed to be so laden with feeling that you cannot help but feel for the protagonist, or agree with the narrator, or listen to the “facts.” That’s what images and music do for us. They’re vehicles of emotion.

Feeling with the person on screen is… not necessarily a bad thing. And: your emotions can most definitely be hijacked into buying, supporting, adopting things outside your best interest if you are not careful. As an educator, I don’t just want you to feel what I feel. I don’t want you to consider me correct because I said it beautifully. I want to sharpen your critical thinking skills and your world-making capacities. I absolutely do not leave emotion out of that! Emotions are as central as the written, verbal, numeric, social, ecological knowledges we are able to gain to navigate this world and the next. I am just… extra cognizant of how much I can lead viewers to feel with me without further thought. The videos of mine that go most viral are ones where I show the most emotion, whatever that emotion is: hopeful, cheery, despondent, grieved, furious, combative. We love emotion. We live such isolated, stifled lives.

The challenge of reading is to navigate the narrative without the overtures of overt feelings. There is no face to latch onto, no music that sways you. Words on a page especially cannot compete with screen-time. They’re not meant to. The boredom opens up space in your mindscape to your own thoughts, opinions, and feelings.

Listen again: reading is still uncomfortable in certain seasons of life, especially seasons that require high screen time from me. I still have a week, two weeks go by without reading. I still pick up a book and blink and realize I’ve spent forty minutes on my phone. I read specifically because I notice how much my brain expands his capacity when I force him into the mode of expansion. Expansion is itchy! It’s uncomfortable!! Reading does not always feel good, just like going to the gym or doing your dishes or eat vegetables does not feel good (especially if you haven’t done it in a long time) and yet!! I sigh in relief when it’s been done. When reading defines my habits, I think noticeably easier.

I read too because I witness, on the other sides of the world, Palestinian scholars, journalists, poets be exploded, entire universities be leveled be swept from the earth. I witness the most internally displaced people in Sudan be a population of children, who may never read and write because of what their world becomes. Colonialism necessitates systems of education turned to rubble so that they alone make the stories and the images and the vehicles of emotion. And we in the United States buy into the lie it’s just coincidentally “too hard” to read.

Some of the people that galvanized me the the most did so through the use of words. the words of revolutionaries. especially poets. my first love was poetry. One day we’ll read the poetry of Assata Shakur and bloom together. Today, this essay already grows long.

Finally: Short-form video entertains more than it sticks.

I have grown to detest short-form video as a means of learning, specifically because these insidious apps. As previously stated, I am a proud member of Gen-Z. I have watched, at this point in my life, hundreds of hours of educational content: everything from Ted-Ed to Crash Course to ASAP Science and many in between. It feels good, fun, rebellious even, to use my screen to learn. Even though I personally did grow up utilizing atlas books and encyclopedias in schools, I still ended up at the computer lab regularly by sixth grade. I am one of the last of my kind to never have an iPad babysitter because that technology was not widely available in my community yet. We had a computer room and dial-up internet until I was a teenager.

And yet still, the vast majority of things I spent all that time “learning” in short-form video, I could not tell you now. I have stronger retention of the maps I hand-drew from a world atlas in the fourth grade than I do of the internet games we played to learn geography. I can tell you the thesis and central arguments of a book I read two years ago. Of most of the books I read two years ago. Or a documentary I watched two years ago. A podcast project, an album I listened to two years ago— all of these methods of learning required long-form attention.

Can you tell me the thesis and supporting arguements of videos you watched from two calendar years ago? Not just one off that really happened to stick in your memory. Most. Can you tell me most of the claims and evidence made in the hours of videos you watched?

There is no nuanced argument you can explore the heights and depths of by watching someone talk for three minutes.

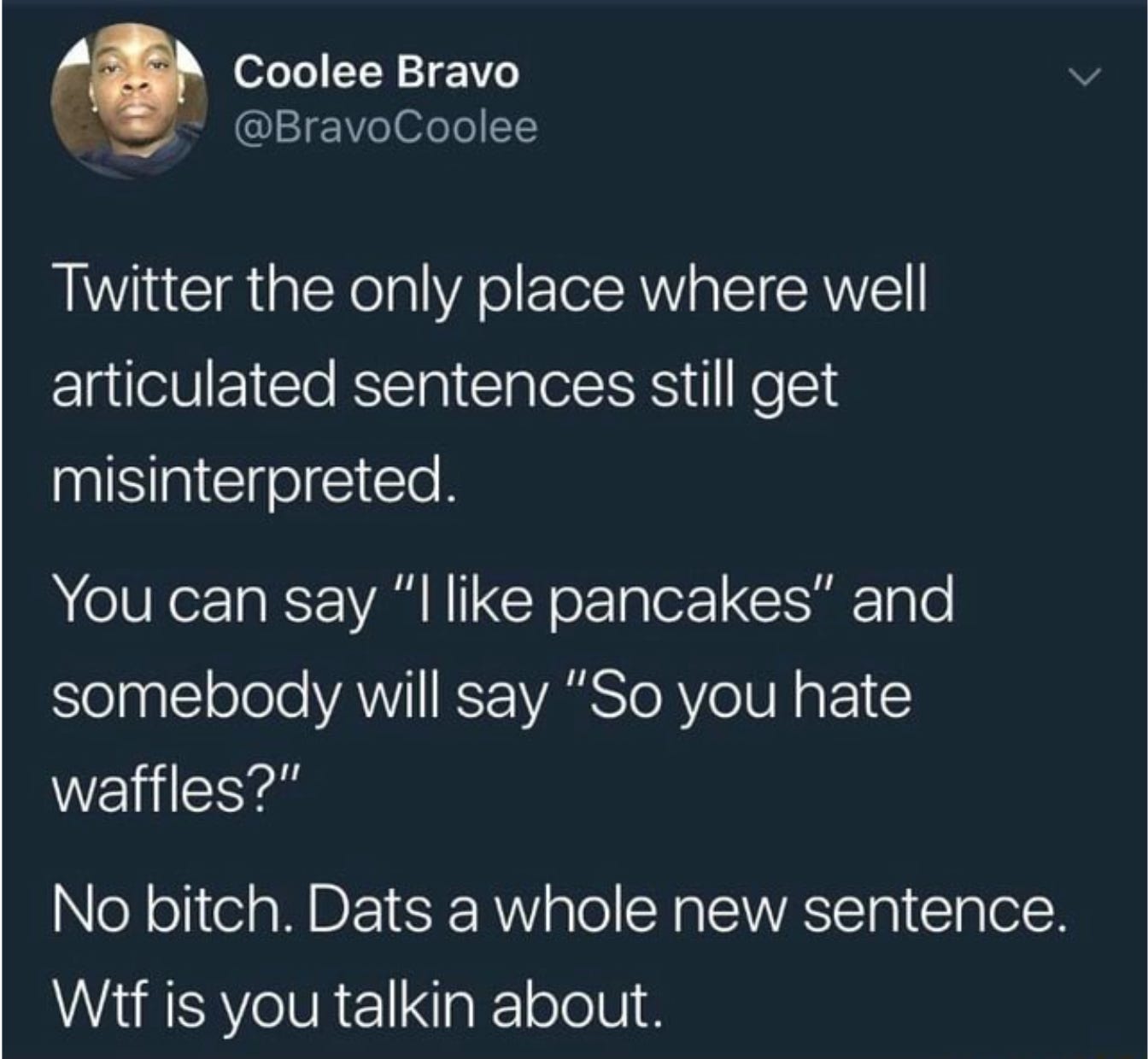

Lord, I love this tweet. It’s true of all short-form media.

In a persuasive essay, one nearly universally found section of analysis is that of the rebuttal— where you anticipate your opponent’s claims against your theses and springboard back into stronger arguments for your own affirmative. This section necessitates self-critique and also creates the groundwork for critique that is actually capable of moving us forward.

Unfortunately, I have to use this section to rebuttal critiques that are lack-fucking-luster. Every time I say something like, “Reading is a keystone of liberatory praxis,” someone accuses me of worshipping the written word. I say, “short-form video does not teach us as much as we think it does,” someone else informs me gently of “the importance of indigenous storytelling,” as if it might be the first time I am hearing of such a thing, and as if all the indigenous people of the world are placed into one big groupchat.

In reading this far essay, you have already learned about me that:

(1) I personally, by way of dyslexia and other neurodivergence, benefit from alternative learning methods. It’s why I read all of my essays.

(2) I am indigenous.2 [Additionally, Black American traditions include oral methods of survival heavy, considering it was illegal for us to read for most of our existence in the United States.]

(3) I dedicated my undergraduate thesis work to oral history and storytelling because of widespread rural illiteracy in Sierra Leone (my country of origin and also much of my family).

While I would normally use the rebuttal section to grapple with better researched critiques, I instead must review my own work because short-form engagement did not give said critics the time, space, or incentive to root their critiques in research of the author. Because all of the above is publicly available information previous to this.

Bite-sized thoughts— especially short form video— convince you that the whole thing is right in front of you. I am trapped in an academic zoo, wherein I produce thoughts or emotions or projects what have you and often receive nothing meaningful back. The critique I receive on TikTok and Instagram… just… constantly lacks basis. Disappointing! Lackluster! I like to be critiqued. Critical analysis allows artists to take more compelling, cutting, bitter cunning shape. Short conformity stunts our conversation to the length of your attention span. This undermines the communion between artist and muse.

Short form video specifically captures the audience by what they feel, not necessarily what they wish to know. The reason my musings on reading (and the lack thereof) had no trouble being viral is because I made it at my wits end. I cry a bit on camera even. people respond with the way they feel having seen it— and more people saved the video than read or listened to any of the essays mentioned. Feelings are important!

And.

Short form video land finds its successes in giving you the fullness of the human experience back to us in bite sized pieces— almost like an emotional ventilator. it does not require you to concentrate. It doesn’t require you to do anything but receive the educative words of someone who more than likely read and engaged in long-form researched to make the video that you’re watching.

Do you know how much your oppressors read? Do you know how much they read?

conclusions: reading, then, is a crucial act of resistance.

Not the only way, or the primary way, but a mode of literacy we must not negate or shy away from. Reading and writing are disciplines distinct from other forms of literacy: aural and oral proficiency (speaking and listening), media literacy (video watching, noticing ), financial literacy, social literacy, numerical literacy (shoutout to the baddies with math anxiety rooted in the same oppressive upbringings). There are histories, blueprints, stories we can only access through the pages they’ve been printed on. If that was not important, we would not lock university libraries behind several hundred thousand dollars paywalls. If there was not agency and power to be found in reading, the empire would not work so hard to burn your hands away. If video learning is truly as harmless and neutral as we think, why are there screens everywhere in this world? Why are there so much advertisements, so much incentives, to spend all day looking at someone else making you feel?

Can you see the seams? Have you ever walked around outside and tried to see how long it took you to look at a screen? Why are there screens every place you turn your eyes?

I, ismatu, the narrator— I am a person who marvels at the freedom dreams of children, and the youngest ones reach for books with excitement. I am a person who sees clearly that the world we’ve had for the last several hundred years as it crumbles— violently thrashing, like a drowning man, or the vacuum of a sinking ship—the desperation becomes more intense, targeted, flails to take everything it can down because it knows its going under. I want you to consider this world’s collapse inevitable. The question remains: what happens after this one? who is being born? will we be here to catch that baby, this newborn world and raise it up for us? for our kindness? for the sake of our love? or will this world be worse than the one leaving?

make yourself an enemy of hopelessness and complacency. do not listen to the voices, internal and external, that tell you you cannot. you can. read. read. read. you must.

for me. and the children to come after us. because if we can’t read, what chance will they stand?

I hope the words, and the work, of your day pass through your hands with ease.

or, simpler said: peace.

ismatu g.

Jazz of the Episode:

The Jordan River Song x Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru

Lena’s Song x The Sweet Enoughs

Sunset and the Mocking Bird x Duke Ellington

Abusey Junction x Kokoroko

Udo x The Cavemen.

Muziqa heywete x Getatchew Mekurya

Mogoya x Oumou Sangaré

Drume Negrita x Andy Bey

Tony x Larry Morezo, Dennis Tini

Melancholia x Wynton Marsalis

Spring Yaounde x Wynton Marsalis

I make this US-American specific for the following reasons: it is my birthplace and the site of my raising, because the majority of my non-reading constituency is US-Americans (folks in other countries are literally translating my work to one another), and because I wish to shine light specifically on the myth of the educated West. The West does their damndest to make sure lasting, expansive education is only for the rich and their lapdogs. The rest of us only get enough education to be effective workers— it is not expansive at all.

Can you tell me what indigenous tribe I’m from? For all the viewers that swear they have such high retention? Everyone remembers the tractor, no one remembers the tribe.

Share this post