Introductions

To my lineage, to my family, to myself and to you all, this work is the beginning of the rest of my life. I will see a free and fed Sierra Leone in my lifetime. No child of Africa should ever be hungry— not when our earth is bountiful like this.

If you’re reading or listening this, that means I’ve decided to pull back one of the veils of my life and tell you a little bit about my family history. My name is Ismatu Bangura, I am a Sierra Leonean Black American, and I am also the granddaughter of Paramount Chief Alhaji Bombolai [may he rest in peace].

I wanted there to be a world where I never needed to bring this up. I would really like to think that I’m special— I would like to think that I would have turned out this way, this fiery, this mobilized, even without politically active parentage. And I just don’t know that that’s true! I think it might be disingenuous for me to pretend as such. Being born into a family where people cared deeply about the fate of the world is a privilege. Hell, being born to two parents that loved me and that wanted me and fought for me is a privilege. Much less being born to folks in sincere positions of authority— parents who still, to this day, are in the position to be able to care for tens of villages at a time? It’s the reason I can help solve these problems on behalf of my tribe as a whole. It’s the reason I’m certain of our success.

I also think in failing to share more about who I am and who I come from, I make myself overly intellectual. As I said in essay one, I am not this way because I read about oppression in college. I am this way because life has taught me the skills of my hands. How can I teach without talking about my teachers? How can I ask you to mobilize without sharing who and what makes me move?

I’ve been angry on the internet in recent days a lot, and I don’t like to make a habit of it. There are a great many uses for anger; I’m not saying that anger is bad or unproductive, and I certainly don’t regret it. Anger is just, at the end of the day, not the force that compels me to act. Anger is not the thing that gets me out of bed in the morning. When I run on spite or righteous justice or vitriol, I notice that I burn out fast. The steady drum that keeps my hands steady, my head focused, my heart beating— that’s love. I am compelled by love for my community to act.

I share with you today a recorded conversation between me and my father, where we talk about the realities of living in Sierra Leone— a country where food insecurity is the norm for most of our citizens. We also talk about his father— less about the chiefdom and more about the kind of man he was. This will likely be the first of many conversations that I’ll share about him and his life; I am so blessed to have him. I have lost so many loved ones— including Grandfather Bombolai, who died long before I was born. I am so grateful for the opportunity to love and learn from my father in adulthood, and I want to document and share as much of that process as possible. Let me know if you have any questions you want us to answer!

What I am learning right now is that good organizing is transparent, it is ongoing, it is inter-generational and it is deeply personal. My skin in this game. This fundraiser is the first thing on my mind upon waking and the last morsel of thought before bed. It’s like I’m in love. I keep dreaming of how much my grandmother will dance when she sees what me and her son will have done.

Listen as my dad and I discuss the current state of things. Transcript below.

A conversation with my father: January 16, 2023

Ismatu: So when you say “high cost of living—”

Abu: Yes.

Ismatu: —you feel like the cost of living is higher in Sierra Leone than it is in the United States?

Abu: Well, you see, if you’re receiving the hard currency, the dollar, it’s not so bad.

Ismatu: Right.

Abu: But for those who don’t know or have no friends or nobody overseas who’s helping them with dollars, it’s very expensive. So, there are many families there who are not even able to put one decent meal at the table because everything is expensive. They can’t afford meat. They can’t afford chicken. They can’t eat eggs. Because it’s all expensive! There’s no balance nutrition, and that kind of stuff. So that’s what [Uncle] Daniel meant when he said, “well if you’re going to go back, to do these things, you have to remember the high cost of living and all of that.”

Ismatu: High cost of living?

Abu: Yeah. Because everything is damn too expensive1 and it’s not easy to manage.

Ismatu: Unless you have dollars? Like the Leones [local currency] are never going to cut it.

Abu: Yes. Say, for example, somebody who has a wife and, say, four kids with him for a family of six and he makes $25? A month? How is that livable? And it’s not even enough to buy a 50 pound bag of rice, which is their staple food. They eat rice every day. Some of them, they could’ve been eating a whole lot of things every day— if they haven’t eaten rice yet and you ask them whether they’ve eaten, they’ll tell you no. Because they haven’t had rice! That’s their staple food. So, a man with a wife and four kids cannot even make enough to buy a bag of rice, which is their staple food. Well, imagine: school. Regular meals— you can forget about three meals a day. Even one decent meal at the table every day, it’s a problem. So how they’re managing to do this— I’m telling you, they’re starving. Hunger and starvation out there. So I said to him, I don’t even want to take— even if I have it, I don’t want to take a whole bunch of money and put it in my pocket and go, because it’s going to be gone. Very quickly. I would rather put it in machinery. To help the people! I’m looking for economic relief. If we put it in the machines that we’re buying now to help the people, it will give them jobs, and also we will be able to achieve the things we want to do— like building those desks for the school kids, you know. The agriculture thing. And so it’s going to benefit a whole lot of people. So I would rather benefit and put money in the machineries then take it with me, because I can live with them the way they live. I’m from there. So whatever monies we’re gonna be making from these investments, I should be able to have— to live on it, or some of the proceeds just alongside them. But frankly, $1000 a month for me and Sierra Leone would make me live a very good life. But $1000 a month in the United States? That’s not even enough for rent.

Ismatu: But, jobs that pay $1000 a month in the United States? Everywhere.

Abu: Right.

Ismatu: Even though that’s a slave wage here, and you would absolutely be living in poverty and you’ll have three roommates, you still have access to the structural privileges of living in the United States. There are roads basically everywhere. You have Walgreens. Like, even if it’s expensive. How many jobs are there that give $1000 a month in US dollars based in Sierra Leone?

Abu: in Sierra Leone? Not many.

Ismatu: Not many.

Abu: The politicians only.

Ismatu: *heavy Negro sigh*

Abu: The politicians. Business people are able to realize that. But in terms of real employment, whether in the private or public sector or governmental things, or NGOs, it’s impossible to make $1000 a month in Sierra Leone. You have to be based in a job where you have access to stealing money without getting caught. Otherwise, no way.

Ismatu: So it’s a system where corruption, if you want to live like a “good life,” is necessary?

Abu: Absolutely, yes. And the corruption is there anyways. That one, I can’t even begin to speak of it right now because it would not end.

Ismatu: Well, so what’s interesting is— you told me growing up that your father was a politician. You said, like a politician.

Abu: Yes.

Ismatu: And I remember being very confused, because in the same breath, you would say, “He was one of my biggest heroes.” And I used to say— I mean like, African children, we figure out quite early why were here. Why everyone at home speaks one language, but everybody in school speaks another.

Abu: Right.

Ismatu: It’s not like you and mom told me about the reasons that you immigrated to this country when I was a child. That came more when I was a teenager and adult. You never really even addressed her lives before me and my sister happened.

Abu: Right.

Ismatu: But sometimes you would tell me about your parents when you were children, and it sounded like… honestly a similar life to my life in the United States. So, you start to put together, “Okay, so why are we so poor when my parents, just when they were kids, lived a life that sounds like the life I’m living here?” And we find out about corrupt politicians very early. So imagine, I was sitting here like, he says this man is one of his biggest heroes, but he’s like a politician? What does that mean? That can’t be. But you didn’t mean politician, did you?

Abu: Well. There is a difference, yes. Yes. Well— if you are… if you’re the paramount chief. The chief over the chiefs among the chiefs and something like that, and you have many other leaders under your command, in a way, you’re a politician. But—

Ismatu: He did not work for the state.

Abu: But that’s different.

Ismatu: Very different!

Abu: He worked for his chiefdom. Not for the state. But the chiefdom is under the state anyways— this is not making any sense, I need to write some of these things down.

Ismatu: I mean, it sounds similar to the way that indigenous lands work in the United States.

Abu: Imagine the United States has the federal government.

Ismatu: Right.

Abu: And then they have the states, and the states have the counties. It’s something like that. Instead of we saying counties, we have chiefdoms. So my father was paramount chief, and presided over a big land that has several other chiefs under him. But he was the boss. I’ll take you there. You’ve been to Sierra Leone twice; unfortunately you did not even go to where I came from.

Ismatu: I know :(

Abu: Because you have no need to go there!

Ismatu: No.

Abu: Unless to sightsee. Your program didn’t call for that area2.

Ismatu: Yeah.

Abu: So. Oh, I can’t wait to take you there.

*after the happy silence of eating*

Abu: You can turn it off now.

Ismatu: Actually, I have one more question.

Abu: Okay.

Ismatu: So, when you say your dad was like a hero to you— well, he wasn’t like a hero to you. He was very much a hero to you. Do you feel like you’re still following in his example or in his footsteps?

Abu: In a way. He was a good provider. He was Muslim, by the way. He was a Muslim with many wives— more than two dozen wives. That example, I will not follow that. But in a way, he’s still my hero in the sense that he was a fair man. Fair in the sense that, when he judged cases between people who were litigating against each other, he tried not to be biased. In that sense, he was a very fair man. I witnessed some of those things myself. And he was a caring, loving, truth-loving man. And he was humble. I don’t know if I told you this, but I remember— you see the thing is, when I was little, even if I do something, and I’m guilty because I was caught red-handed in the act. If they allow me to speak, I can free myself. With all kind of lies. So my father, knowing that, and knowing I was always guilty, he didn’t know what to do with me! So one day, my sisters lied about me and my dad beat me up without asking. Because he knows, as usual, I’m guilty anyway. So what’s the point of going through the motions of trying to interview me to investigate? Because I’ll be guilty and free myself if I’m allowed to speak, and he didn’t have time for that that day. So he whipped me good! And then the next day we went to school, and then he found out that it wasn’t true. So, as soon as we came from school, he sent one of his policemen to go get me. And I’m thinking, I’m going there fear and trembling like, oh what did I do? What have I done? And this was uh— he was in court with so many people. His entourage, people around him. As soon as I stepped in, he went down on his knees. He said, “I’m sorry, my son.”

Abu: So he said, “I’m sorry, I was unfair to you. I should have allowed you to speak yesterday, so I’m not going to make excuses. Yes, I am your father, but I shouldn’t have done that. Would you please forgive me?” All the way on his knees and hands. And then he said, “Put your hands behind my head.” Because for them, when someone is on your knees, begging you, you put a hand behind their head, that’s a sign that— that signifies you have forgiven them. He said, “Put your hand behind my head.” At the time I was shaking, you know? Because at the time, some of his entourage guys, they were shocked by the behavior and ran out of the court! You know? So I’m crying, I’m like, “No, Papa, no.” And he held my hand and put it on his head, you know? And then he got up, and he gave me twenty cents. $0.20 at that time was a lot of money. Do you know, okay, cube of sugar? It’s bigger than the cubed sugar is that I see here.

Ismatu: Yeah, the big ones!

Abu: Yeah, St. Louis!

Ismatu: Yes!

Abu: A blue box.

Ismatu: Yes!

Abu: it’s 30 per row and there are three rows. So that’s 90. I went and bought two of those boxes.

Ismatu: Oh my gosh.

Abu: Two of those boxes! And I sucked all that sugar. I ate it all! In one day! So we’re talking 180 cubes! Any of my friends says to me, “can I have it? Can I have a sugar?” I would be like, “Yeah, so when I was being beat yesterday, where were you?”

Conclusions

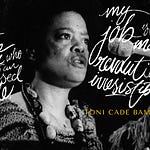

I share this tidbit with you from my father’s kitchen because I believe my personal is political. Identity Politics have gotten a bad wrap since they’ve been bastardized by the right— forming your politic based upon your identity was never about standing blindly by whoever shared some few characteristics with you. As the Combahee River Collective made clear in their seminal statement:

We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else's oppression.

All of my doing: my videos, my essays, my fundraising, my organizing, my scholastic achievement— top to bottom, everything that I do is compelled by a politic of love. The center of my will to act is about love for my most beloved. I am in the fortunate position where I have adults close to me that I can look to as examples for how to invest in your own community and adults that teach me just how many ways there are to love somebody. How economic justice is love. How food sovereignty is love. How a commitment to honesty and to transparency, humbling yourself enough such that you are willing to learn from everyone (including and especially children) are loving acts of the highest order. As I continue my life in public, and as that life becomes increasingly political, I want to make clear that the keystone of my politic is a love that compels you to action.

With all that being said, thank you all so much for your donations. Thank you for getting us to the halfway mark. There has also been a section added to my link tree called Financial Transparency, where you can see our expense spreadsheets, our money flow, and any other financial things we want you to know. As of today, Saturday January 21, we are making arrangements to buy a tractor for my family. We have raised $58,574. We still need to get to that $115k mark so that we can secure the rice harvesters and housing for our animals, but we’ve done so much already.

Glory to God and the splendor of the earth. Glory to a love that moves people to act in the best interest of the most vulnerable. Oppressed people will eat until we are full.

In our lifetime.

Ismatu Gwendolyn

my father is unused to cursing in English lol. he was trying to say “too damn expensive.”

I returned twice to Sierra Leone in my undergraduate career to conduct ethnographic research on the Ebola crisis.

17| To High Chief Bombolai; with love, from your granddaughter.