To begin: I think licensure does more to protect the clinician than it does the client.

If you’re here, you’ve probably already seen this viral video where I come out as a stripper and state plainly that I don’t want licensure. Or maybe you’ve been here and hip to things for a while (because truly none of that was a secret). Either way, welcome! Threadings. is a newsletter and podcast where I explore Black feminism, love studies, and other things that hold me together— this essay happens to rest easy in all three aforementioned categories.

Because I need to say this clearly: I don’t think licensure makes you a “bad” or unfit clinician. I do think licensure is a contract with the state that many of us are coerced into signing. It is not an accident that we’re trained to attach legitimacy, expertise, and other metrics of worthiness to whether the state can account for us or not. It’s also not an accident that we tout the ability to report a licensed professional as a positive when most of our clients don’t know how to do that anyways. I want us (social workers and those impacted by social work) to think critically about where and by what mechanism we (social workers) swear our allegiances. I want to provide an alternate story for social work students who are told for the entirety of their education and careers that licensure is the most correct path forward; I do so with the understanding that the vast majority of social work positions available are locked behind state licensure requirements; I ask us to resist this infrastructure anyhow. It is not an accident.

This essay will analyze a mix of academic + long-form texts and personal experiences. It has the following thesis:

All forms of policing carry unnecessary violence and social workers are under the umbrella of police. I understand policing as the coercive hands that use the threat of physical or metaphysical consequence and overhanging fear to compel the actions of the masses away from communal sovereignty and towards supporting racial capitalism (against our own interests). In shorter terms: policing happens through policy, not just a white man with a badge and gun. Because social work was founded with the desire to limit resources to those considered “Deserving,” I commit my work to those of us in the “Undeserving” category— especially as a Black queer sex worker. I am personally wary of the surveillance that comes with soft policing and work to caution us (the public) into presuming benevolence of those of us working for (or in contract with) the state.

Let’s begin.

I. The Origins of Policing and Social Work

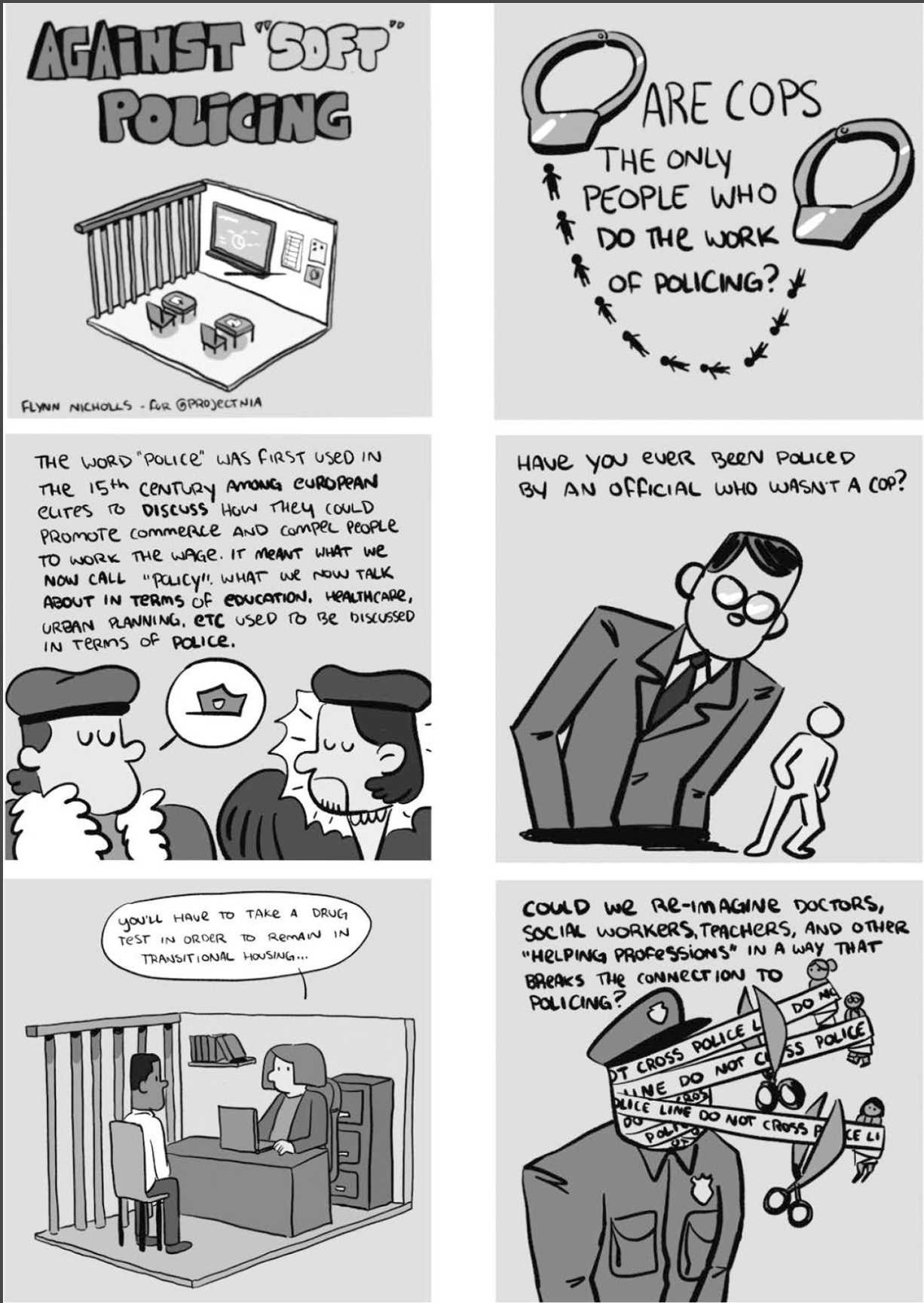

In the panel “No Soft Police!” linked at the bottom of this essay, Mariame Kaba takes her time to speak on the history of capitalistic governance that highlights the connection between police and policy formation. She says it better than I will, so I’ve transcribed her words below (all bolding and emphasis my own).

“…Law enforcement are not the only kind of police, actually. Right? So, this goes back to the point we were making in the graphic about when police comes into being— the notion and the word “police” comes into being. That policing has a deeper history than most people acknowledge. Because the term was first used in the 15th century as part of an elite discussion concerning how the rising states of Europe could promote commerce and encourage people to work for the wage instead of living a life of subsistence. This is when the term police comes into being… because people talk a lot about police and capitalism and those things coming together. But you have to understand: the discussion of what they were terming at the time “police science,” was one of the primary ways that the work of administering a government was talked about until the early nineteenth century. And during this time, police meant what you and I now understand as policy. We call policy “police.” That’s what that connection is here. So, police encompassed various things: administrative science. Public health. Urban planning. And much of social policy today still carries the basis of that old police science. You see the connection there? Soft police isn’t something we just invented in 1996. Right? It’s actually co-constitutive of the rise of the notion of police— in Europe, at the very least.

So, the abiding concern really was the protection of private property. It was the creation of markets. It was the regulation of poverty. It was the separation of the worthy and deserving poor from the “undeserving criminal” element. This is why so many people’s experiences with for example, sometimes public education, sometimes social welfare agencies, can feel so oppressive. Because social policy is not designed to help all people equally— it’s actually a police project to fabricate order and pacify the population.

So there’s a couple things here that are important. The first thing that you need to know is that the system of policing stretches far past active policemen. Policing existed before the construction of the United States, so the functions exceeding slave-catching or the creation of prisoners meant for free labor (although that is a major piece of contemporary policing in the US). The worldwide system of policing designed to change the world order from one where people worked together for local, communal goods and services to one where people traded labor for wages— a system with a profit margin that enriched the elite way faster than feudalism ever could. In order to market such a fundamental paradigm shift, every single facet of society was regulated with a mask of benevolence. The centralized state told us all that regulation in all forms was a good thing; that they alone could ensure that our standards of health, wealth, sanitation, resources, education (etc.) were up to snuff; that without regulatory forces (*eyeing armed policeman* … heavy on the force) we would fall into senseless murder and fires and starvation and anarchy!! Ahhh!!

Note here: the capital f Fear which comes into play when thinking of policy and policing. The idea that we cannot possibly and should not attempt to regulate our own selves shows up in mental health spaces all the time. This is not to say that people skilled in healing are unnecessary— I actually think community healers engage in deeply crucial work. I am saying that in my field, the private practice arena, the gold standard for healer is a professional person trained in formal academic colleges and registered with the state. The ideal we are taught is not an unlicensed community worker and certainly not a *gasp* … life coach. This is where we get that outsourcing of skilled work; healing comes from people that have been trained with state-standardized measures and that’s it.

Under the state’s regulatory systems, both the healer and the person seeking healing are subjected to surveillance, scrutiny, and punishment if they do not comply with the wants of the state. In the case of the healer, licensure makes you a mandated reporter,meaning if the particulars of the intent to harm oneself or someone else (or anything involving the harm of children) come to surface, a mandated reporter is required to contact whatever authority is most appropriate. That almost always involves the traditional or the administrative police. What constitutes as harm is also, then, up to the reporting professional— which can be terrifying and murky for the care seeker. If you (the licensed professional) fail to report, you stand to risk your licensure (read: the ability to work in your field), as well as your current employment, fines, and even imprisonment. In the case of the person seeking treatment, you (the patient) are required to trade personal information** (documentation of your symptoms and diagnoses going on file) for the listening ear of someone who may or may not able to help you long-term.

**Unless you can pay out of pocket to avoid involvement of insurance, of course. Privacy, as most things, is a class privilege.

In both cases, the argument is the same: that nothing less than regulation by the state is safe; that outsourcing expertise is always a better option than whatever care our communities can provide; that the power imbalances of that person being able to report you, document you, or institutionalize you are nothing to fear to long as you have nothing to hide. Therapists absolutely are part of the regulatory network of police science.

I cannot recommend reading the book No More Police! enough. If you’re nervous to read a whole book, consider just the chapter cited in this essay. Or buy it for yourself and a friend from an independent bookstore.1

II. The Benevolent, The Deserving, and The Whore: Social Work’s Origins and its Attitude Towards Sex Workers

Social work in the United States is a doozy.

A quick and dirty on the establishment of the field: contemporary social work in US settings began with the Christian evangelical church providing aid to impoverished communities in major metropolitan areas. Cities across the United States (particularly New York and Chicago) wanted to attract capitalist business tycoons and their heavy-swinging pockets, so they had little tax policies and even less tax enforcement. This completely guts social welfare services. Big Money Tycoons also do not give two flying fucks about the welfare of the people they extract labor from, so child labor was common, easy and cheap. Upper-class Christian white women that felt compelled by their religion rise up to fix the problems of 20th century American society (so I am told). They took a sweeping gaze around at the desolation of the country’s impoverished and dawned their Wonder Woman Belt of Righteousness (or whatever; forgive me for having no stars in my eyes for these retellings. These people were as racist, homophobic, and whorephobic as the day is long). I am sparing you the boring details, but if you would like them you can gon’ head and scroll down to the resources list at the bottom of the essay.

So here is our first important note: resources and aid distribution operate under that same police science of Deservingness, and in social work the qualifications of Deserving pass through the lens of white, Christian wives. Wife here denotes a woman that is a direct beneficiary of the patriarchy (even if they are against male tyranny on paper). They focused heavily on class-based oppression (aid to the poor) and gender-based oppression (aid to women, often women in the societal role of wife— almost always women in the societal role of “white”). Jane Addams wins a Nobel Peace Prize for her work advocating for child labor protections; children are regularly seen as the most Deserving people group around. They (remarkably) did not focus on race-baed oppression, or what happens when race-based oppression intersects with the other kinds of oppressions (gender, sexuality, occupation, etc.).

The Politic of Deservingness follows us everywhere: it’s the foundation of capitalism, the bedrock of meritocracy, and the justification behind unequal distribution of resources, aid, and assistance. It’s one of the reasons that still (to this day) the people groups that benefit the most from public assistance programs are white women. It’s why the face of a white girl child is always front and center for advertisements about sex trafficking, despite the majority of sex trafficking victims in the US and worldwide being impoverished Black, Brown, and Indigenous girls and women. You know, the people that are not (not ever) Deserving of a society turning everything upside for their absence.

One of the foundational tenants of social work policy in the United Staes was the eradication of sex work, which was seen as a blight upon citadels and a smear upon the moral conscience of this great nation. Constant fear-mongering centralizing on the existence of sex work took place; white woman social workers touted the idea that because the demand for sex work existed, this meant that young women would be kidnapped into sex slavery. They were terrified that sex work would become a way to enslave white women. And, in a reality that academic articles are loathe to cite, their husbands were the patrons of the people they were trying to eradicate.2

Thus, the making of the whore: a woman wearing a scarlet red A on her bosom. Less of a person, more of a metaphysical concept: a problem to be solved, a floating, disembodied pussy to be fucked, a mission to save and serve, a nothing to murder. Melissa Gira Grant says it best in Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work.

To produce a prostitute where before there had been only a woman is the purpose of such policing. It is a socially acceptable way to discipline women, fueled by a lust for law and order that is at the core of what I call the “prostitute imaginary”— the ways in which we conceptualize and make arguments about prostitution. The prostitution imaginary compels those who seek to control, abolish, or otherwise profit from prostitution, and is also the rhetorical product of their effort. It is driven by both fantasies and fears about sex and the value of human life. (Grant, in chapter The Police)

In the role of Prostitute, the worker that clocks in and clocks out of their job becomes unable to remove the costume of whore. And whore is a standing in society that is decidedly, perpetually Undeserving. She is conveniently always mute. She does not speak and can only scream for help. The only whore deserving of aid is one that desperately wishes to leave the sex trade, one that performs the proper amount of shame and penance for her soliciting and desires to re-assimilate into respectable community life. Social workers still, to this day, lock aid to sex workers behind isolating them from their sex working communities and forcing them to leave the sex trade. We call this rehabilitation.

Why is this underbelly of targeting sex workers important to the system of social work? Because you can always tell the ethics of an organization based on the way they treat the people in the shadows. Where sex workers call for decriminalization and means of self-regulation, policy makers (policeman) usurp their ability to work safely. No matter how chronic the mask of benevolence is, your politic is most exposed with your actions towards those that no one will go out of their way to defend. In my personal experiences, some of the people that have been the quickest to disregard the needs of sex workers have been licensed clinical social workers. The combination of Blackness, sex work, poverty, and abolitionist praxis have fully informed my decision to forgo state licensure and upgrade my societal status to skilled, licensed tradesman.

III. Therapist’s Role in Policing (Yes, Even Therapists)

When I say that I am an abolitonist, that absolutely and without a doubt includes social work. And yes, it includes therapy as we know and understand it today. There is a perceived benevolence when it comes to therapists— that mask of benevolence I referenced earlier that crucially benefits the police state. We as therapists are taught to internalize this benevolence without firm question. We are a net good for society and for our clients; seeing us will make people better or facilitate their healing; even if therapy can’t be a catch-all solution for everyone, there is some nobility to be found in trying.

I think assuming our own benevolence as practitioners is a danger to ourselves and our communities. Many of us are skilled, compassionate, justice-oriented clinicians who strive to do their best by their clients. For every single one of those people I met in graduate school, there were three more that I winced (and I do mean physically, facially cringed) at the thought of them with any sort of state-sanctioned authority. Thinking that we are “one of the good ones” is not an honest enough assessment of the field. Individual intent does not surpass structural effect. The reality is: we monitor you. Those of us contracted with the state become mandated reporters, meaning there are certain things you cannot tell us without us having to contact authorities or be at risk the consequences. We do ourselves and our communities a disservice by ignoring the power imbalances that come with state backing. More than that, we often allow our own elitism to convince us that the system of therapy we have in place currently is a good thing— that we are a good thing. The fact that we live in societies where community has been so fractured individual people have to trade money or privacy to call a stranger and find a way to cope with their societal stressors is ass. Why are we pretending like this is not awful?

I’m going to take a moment to peel back the veil (that mask of benevolence) on private practice therapy. When I trained as a student clinician in graduate school, I understood the function of private practice therapy as notating the ways one’s habits disrupt one’s productivity. This was oddly framed as “the process of healing” and not “surviving under capitalism.” I am always (always) skeptical of interpretations of the human experience that conveniently justify the current world order, and the positive spin given to the endless forward momentum we promote as growth most definitely falls under that category.

I also experienced the expectation to self-regulate and move on personally, when I endured graduate school during a time of intense grief. I lost so many family members to COVID, stress, poverty, or unfortunate combinations of the above that I don’t even wish to mention the number. I’ve stopped bothering to count; I always forget someone and have to start over. I was housing insecure or homeless on more than one occasions. My school knew about these hardships, as did my clinical supervisors. I was never offered any official bearevement time or any assistance outside of a short-term loan from my university (on top of the student loans I already took out for the damn degree). I was told to just “work through the grief” by my supervisor in my first year. I was not allowed to just quit my second year after breaking down from a significant familial death, even though I had accumulated all the necessary hours I needed for graduation (also coincidentally, a place that chose to charge my clients for meeting with me halfway through the year but also refused to pay me). How to be productive under duress is a central tenant of therapy today because we need to equip our constituents with the ability to endure the weight of this world. We are not trained to teach our constituents that a better world is possible.

A quick soapbox: I think therapy would look a lot different if the goal was to eradicate the systems in place and not justify or survive under them. True justice, true resource allotment, true healing comes from moving away from policing, carcerality, and scarcity and towards reparations, communal living, and community accountability. True justice and healing would have us working a fuck ton less and equipping our own places of belonging with the skills we learn in academy. One’s freedom to heal would not be connected to their ability to work under capitalism. But then, most therapists have signed contracts with the state and are excited about the opportunity to do so... the outcomes don’t surprise me. I just wish to remind us all that a better world than this is possible.

Productive vs. unproductive was also framed as this means of moving away from the sticky mess of morality in therapeutic settings— those pesky Christian puritanical holdovers from the establishment of the field. Instead of behaviors being “good” or “bad,” I was trained to think of things in terms of whether it was productive or unproductive in the life of my client. I was to focus and teach on tools that were designed to give you mastery of your life in acute settings— you know, control the things within your control for better outcomes.

Two things: (1) those tools come at the price of documentation. You know how social media isn’t actually free, you’re paying for it with your data? That’s exactly how I feel about using insurance to pay for session. If someone was distressed to the point of tears, there is a box I check to notate that. If someone’s countenance changes from normal to lethargic or angry, there are boxes to check for that. There’s a line you have to walk of writing down just enough to let my supervisor know what went on in my sessions but not so much that I would get my clients in any sort of trouble. Eventually I just started to pretend that everything was fine, sacrificing what could have been valuable instruction from my supervisor to ensure my clients had some semblance of real, actual privacy. As a therapist using insurance, I was also required to diagnose my clients from session one. I had 50 minutes to meet you, listen to you, and then decide what was wrong with you. What if I was wrong? Did you know that diagnoses can follow you from therapist to therapist, or even outside of that? Did you know your therapist’s notes can be subpoenaed if you ever stand trial? Also (just an aside) if you are seeing a therapist that is employed by your school or workplace, don’t. Just do not do that.

Thing two: mastery is a fucking lie. It’s such a farce. I think the allure of therapy and private practice is the illusion of control— that we have means to change our individual circumstances should we self-assess, plan, and execute accordingly. In this society, that’s really only true for people with certain amounts of structural backing. Remember when I said this essay would be a mix of texts to draw from and personal experience? I’m going to tell you a story.

I will never (ever) forget my first session. My client (whom I still love, and pray for, and hope every day is doing well) was crying with me because she was navigating treatment of her child’s speech delay. I am trying to keep my own self together because my kitchen exploded (???) and I cannot tell her that. She was living in old housing that still had lead in the paint, and because of that her children had higher amounts of lead in their system than what was recommended. I was living in an old house that had so much water damage in the kitchen the cabinetry fell from the wall.

Picture this. Her, the patient: crying with me because her children have lead poisoning and she feels like a terrible mother, when the fault of the situation was poverty (and thus, the government). Me, the clinician: holding back tears because she doesn’t know how deep my empathy goes. Because I am living in a barely-legal apartment trying to afford the ability to work for free in order to get my master’s degree. Because even though I know I am still wading through poverty now, I am on a track of life that will catapult me into the next kind working class— the licensed professional instead of the “unskilled” laborer. I will have money to solve my problems and she will continue to call me about the issues of poverty that show up in hers. And I will teach her tools about mind regulation and breathing and journaling. And I will have had the money to solve my problems.

In every piece of employment I’ve had, I experienced this movie-moment where the lightbulb went off. Where I zoom out and watch my life unfold like an audience member in a theater. Where I see myself say, “…oh. This is dystopian. I live in a dystopia.” This moment here, almost crying with my client, was mine in terms of therapy. I never recovered.

My training to give this woman “mastery of her life” is a farce. My mastery of my life was a fucking farce. I am not saying your mindset does not matter, I am saying CBT does not fix lead paint in your house. DBT did not fix the fact that I could see a hole in my kitchen floor that led to outside. You know know what fixes the problems of poverty? Competent and long-lasting poverty eradication efforts. Safe and affordable public housing as a right. Expanded welfare and Medicaid until we have universal healthcare coverage. Eradication and abolishment of debt slavery (read: student loans). After that session, I asked my supervisor if there are any resources I could connect her with; I knew from previous placements that I had that databases exclusive to Licensed Clinical Social Workers exist where you can search for public assistance programs (because of course centralizing these opportunities and making them available to the general public is far too easy). She said, “…yeah, we don’t really do that.”

And do you know what? She was right. Resource connection truly is out of your job scope as a private practice clinician. You would exhaust yourself and burn yourself out trying to connect each of your clients to possible fixes to their problems— because that’s the thing about aid, it’s not a guarantee. I would fail out of school trying to give meaningful, substantive aid to my clients outside of coping mechanisms and conflict resolution. No, you cannot conflict resolve your way out of poverty, but it was truly all I could do. That’s when the reality of the job fully sank in: we are the administrative police. We document you and we train you in regulating yourself so that you do not do anything rash. We are ultimately in service of the state. Here’s that original thesis: licensure does more to protect the job security and the perceived legitimacy of the clinician than it protects the health or privacy of the client. Licensure cannot protect a clinician from saying a bad thing about you; it can only make sure that they (could) receive punitive measures for stepping out of line. The only thing that protects clients in this industry is praxis, and we know for damn sure that praxis does not come from state-administered registration or tests.

We protect private property and the private property is you. You, the worker bee, the community member, the tired and frightened child, are the property of the oligarchs who we feed with our labor. Nothing has changed. We make sure that you are regulated enough to continue in the game of capitalism instead of encouraging you to aid in the struggles to eradicate it. Contemporary therapy and psychology focuses on being regulated, sustainable coping mechanisms, and staying productive. Why would we not want to take away the problems that everyone has to keep coping with in the first place? We, the trained-in-academy healer, give you to the tools to make sure you can keep working. Private practice therapists lack the equipment to help the people at the bottom of our socioeconomic hierarchies move the boulders out of their path. Because we cannot actually do that. If we did, we would work ourselves out of a job.

IV. Conclusions: Healing Individually is Overrated.

The way we go about mental health in the United States is still quite carceral. The only resale protections that come with seeing a licensed clinician is the idea that you can report them if they something wrong. So that’s that same model of policing right? It doesn’t stop harm from happening to you, it makes sure that you can call someone to punish them if that harm happen. In addition, “Go see a therapist!” as the height and depth of what healing looks like to the layperson and is ass. Just entirely inadequate! What’s present is that same structure of carcerality: someone else, out of sight, away from me until it can be productive again. “Go to therapy already!” has become a Twitter retort for people behaving poorly. We treat therapy like the grown up version of time-out.

Under capitalism, the idea of expertise is designed to destabilize community and community knowledge. This is not to say that experts of their craft are bad, not to be trusted, or shouldn’t exist— I am very pro-expert. It is to say that there is far more than one way to be an expert. There are multiple ways of knowing. The “see a therapist” cry posits that we are not, cannot, should not be responsible for each other’s well-being. I could not agree less. Most of the wounds that I work on with clients happened in community: in family systems, churches, schooling, other governing bodies. Our individual problems reflect the issues we have as bodies of people. Knowing this, I am then of the opinion that seeing a therapist and healing individually, while helpful for understanding oneself and learning coping mechanisms that you really do need to survive this world, only go so far. The true test of healing occurs when you are placed back into settings designed to foster love, connection, intimacy and long-term affection. Outsourcing your problems can’t be the only way to get better if we are to make a world where we actually can rely on each other.

At Allafia Coaching, I am using my academic and experiential training and seeing Black folks in groups. The idea is to equip a community of people with the means to care for each other so that one day they don’t need to pay to see me. If you got all the way to the bottom of this essay and said, I hope and pray this person is still seeing clients so that I may see them, click away!

Thank you for reading. I leave us with some benedictions: I hope that we see the structures of policing in the truth of just how vast they are. I hope that clear sight leads us away from panic, disillusionment or despair and towards the will to make friends that can help us pull the new world in from the floating horizon. I hope that you find a village to heal in better than the ones that harmed you. And, as always, I hope the work of your day passes trough your hands with ease.

Ismatu G.

Long-form resources in this essay include:

No Soft Police! Event Recording organized by Interrupting Criminalization

"No Soft Police,” a chapter in No More Police! written by Andrea Ritchie and Mariame Kaba (please email me if you would like assistance accessing the text or if you would like to buy the book for someone else!)

Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work by Melissa Gira Grant, journalist and former sex worker

Brown, Victoria Bissell. "Sex and the city: Jane Addams confronts prostitution." (2010).

Mendes, P. (2020). Tracing the origins of critical social work practice. In Critical social work (pp. 17-29). Routledge.

History of Social Work in the United States

1 curses upon Amazon every day and all day <3

2 White women stay mad. If I had a dollar for every time I saw a white wife just steaming at the club, I could have paid my tip out for the night every single night.

Share this post