Beauty Talk: the Jezebel, the Mammy, and the third gender of "Black woman."

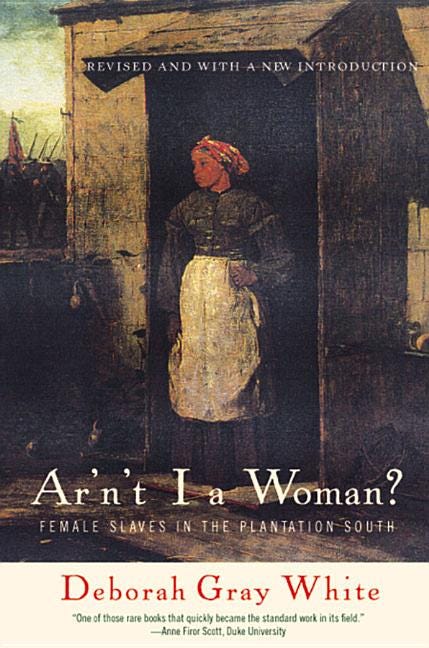

Chapter one review of Deborah Gray White's "Ar'n't I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South" with the question: what makes us so attached to Beauty when it was designed to suffocate us?

an essay formerly entitled, “The (un)intentional making of the Black woman.”

This essay is meant to serve as a supplement to the Beauty is Bad Bookclub that happens every Sunday at 4pm PST. We are getting ready to read through Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness after one more preliminary text, Fearing the Black Body by Sabrina Strings (next week’s essay). Join us if you’re able! Here is the link to the syllabus with the recurring meeting link. I recommend purchasing Belly of the Beast here. If you cannot afford the text or wish to sponsor the text for someone else ($16), PLEASE email me! No reader left behind!

Content warning: discussions of sexual violence, sexual assault, violence against Black people.

Listen to the essay here:

Introduction

In order to really interrogate Beauty’s relentless, parasitic hold on us, we first must understand: “Black woman” is a species that was never supposed to exist.

Book club last week was a wonderful and generative time. Ugh. I cannot wait for Sundays now. After everyone left, an internet friend named Suzanne asked me:

Why isn’t it capital “b” Beautiful until white people do it? Why does Blackness have to get laundered by white faces, white bodies, white agendas in order to be considered marketable?

Now this is inquiry so rich in answer I wanted to pose it to us all. Let’s begin with brief historical review of the process of colonization. I recommend reading the introduction and first two chapters of Ibram Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning if these ideas are unfamiliar to you.

When the white, the wealthy, and the genocidal decided to engage in the most horrific version of world domination possible, they did so by remaking the word “human.” Humans deserved safety, community, rest, space, self-determination. Humans had access to certain inalienable rights bestowed unto them simply because they existed. Human peoples were white, exclusively.

Whiteness was never and still is not a substance on its own, but as a response to what Blackness was (or what Blackness was created to be).

Blackness, the black race (before Black people coagulated into an intentional cultures and subcultures), was meant to embody everything that was brutish, bad, abhorrent about the lowliest forms of a homosapien.

Blackness was not only decidedly bad, it was impossibly so. “Black” was ugly and ape-like and deeply undesirable… while simultaneously sinfully lustful and animalistic in their sex drives; blackness was lazy and stupid, yet conniving and tricky. For all its inconsistency, black was designed to be the parts of humanity that human people should always try and rid themselves of; the less you are like Black “people,” marred and made different by their melanated features, the better.

Where Blackness was the call, whiteness was the response. Blackness was created to justify the slow, self-sustaining genocide of slavery because Black people (under the defining pen of the white, the wealthy, and the genocidal) were not people at all— they were the waste and shame of humanity wrapped up into a meat sack; only good for and made good by slaving for them (Kendi 2016). Whiteness was a mockingbird, parroting back pureness where Blackness spewed dirt, embodying smooth, thin grace where Blackness was bulbous and endless, indistinguishable flesh (Coates 2015). Whiteness’ amorphous and ill-defined state is purposeful; there is negative space at the core of whiteness; the race itself needs to be able to stretch and gobble up other ethnicities into its fold just so that it can continue to exist.

Humans have a right to exist only applied to white folks.*

*…with some terms and conditions.

“Although much of the race and sex ideology that abounds in America has its roots in history that is older than the nation, it was during the slavery era that the ideas were molded into a peculiarly American mythology. As if by design, white males have been the primary beneficiaries of both sets of myths which, not surprisingly, contain common elements in that both blacks and women are characterizes as infantile, irresponsible, submissive, and promiscuous.” (Gray White, 27; emphasis mine)

Not all white people were created equal under whiteness. Yes, there were hierarchies among ethnic background (Bonnett 1998), but this essay focuses on Beauty, and thus, of course, on gender. White men also defined contemporary fashionings of gender in their quest to build their own religiously pure paradise (read: white, Christian fundamentalist, ethno-state)— a paradise, of course, of which they are crowned kings. The same whiteness that defined who was and was not human also created the confines of gender:

man, who could be determinate and defined on his own personhood, and

wife, whose identity was always wound about her free-standing husband.

Whiteness, amidst selling flesh by the pound or a home for a scalp, became obsessed with quantifying a person by how much they deserved to exist. Like capital acquisition (land and labor) became the standardized route to generational wealth, Beauty became the standardized system by which a prospective wife was weighted. If white was the qualifier of human, gender was the further inquiry: how much? Each white person is worth something, sure— but how much?

All the women are white, all the Blacks are men…

The black woman’s position as the nexus of America’s sex and race mythology has made it most difficult for her to escape the mythology. Black men can be rescued from the myth of the Negro, indeed, as has been noted, this seems to have been one of the aims of the historic scholarship on slavery in the 1970s. They can be identified with things masculine, with things aggressive, with things dominant. White women, as part of the dominant racial group, have to defy the myth of woman— a difficult, though not impossible, task. The impossible task confronts the black woman. If she is rescued from the myth of the Negro, the myth of the woman traps her. If she escapes from the myth of the woman, the myth of the Negro still ensnares her. Since the myth of woman and the myth of Negro are so similar, to extract her from one gives the appearance of freeing her from both. She thus gains none of the deference and approbation that accrue from being perceived a weak and submissive, and she gains none of the advantages that come with being a white male. To be so “free,” in fact, has at times made her appear to be a superwoman, and she has attracted the envy of black males and white females. Being thus exposed to their envy, she has often become their victim. (Gray White, 28; emphasis mine)

The rules of gender follow suit: women worthy of protection are not just white (by default). They are also Beautiful, which comes with a series of semi-impossible paradoxes: soft enough to need rescuing but strong enough to run a household, hardworking but never callous-handed, demure and chaste but still desirable, fertile, constantly pregnant by their husbands. The vision of Beauty, which of course had physical attributes as far from blackness as possible, came inherently tied to worth. Humanity (safety, community, protection, resources, etc.) for women was earned not just in their whiteness, but in the amount of Beauty they had: in how suitable a wife they could mold themselves to be.

“In the antebellum South, therefore, ideas about women went hand in hand with ideas about race. Women and blacks were the foundation on which Southern white males built their patriarchal regime.” (Gray White, 58)

Prescribed gender roles follow Afro-descended men into the new race of blackness without difficulty: hard-working, tireless, strong, emotionless, dominant. Violent when justifiable (and, under patriarchy it almost always was). Then or now, contemporary maleness does not give men of the black race any favors, except to structurally place them at the top of their reconstructed households. The man figure as defined by white, cis, heterosexual patriarchy is exaggerated by blackness. The demands placed upon Black men can be harsher, more stringent than their white peers— especially because they were made in part to strip Afro-descended men of the previous sexual freedoms; they had to force the nucleic family model. But blackness and maleness are not in conflict. They do not negate each other.

“Black” and “woman,” however, were quite literally antonymous.

Enter: the Rise of the Jezebel

Black women were not and could not house the identity “woman” due to how much the work of slaving masculinized them. The first chapter of Ar’n’t I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South by Deborah Gray White highlights the many arenas where blackness eroded the possibility that Black women could be women under enslavement. Field toiling meant their physical strength had to mirror or keep up with their male counterparts, designating them too strong for the daintiness of traditional femininity. They were expected to keep up this work even while pregnant or nursing. The auction block commanded nudity as their bodies were displayed, prodded, and groped so that sellers and buyers could ascertain how many children she was able to produce; such practices were incredibly effective at eroding their privacy, right to bodily autonomy, and painting them as promiscuous (as if they chose to be on display); public nudity was especially countercultural to the antebellum south, that covered (white) women from neck to wrist, wrist to ankle. The whippings they received required them to be naked and bleeding as public spectacle; even the nature of receiving corporal punishment, on their backsides, on the ground on all fours had distinct sexual overtones. In fact, the constant display of their bodies was taken advantage of by white men, who sexually coveted them and wanted to justify their abusive, wandering hand.

White men justified their rape of Black women and their sexual subjugation by further characterizing them as seductresses that bewitched them into being taken advantage of. They created the narrative that female slaves were sex hungry and in constant want; they fabricated and projected the “choice” of promiscuity onto the women they enslaved so that it was impossible to rape them.

“One of the most prevalent images of black women in the antebellum America was of a person governed almost entirely by her libido, a Jezebel character. In every way, Jezebel was the counter image of the mid-nineteenth-century ideal of the Victorian lady. She did not lead men and children to God; piety was foreign to her. She saw no advantage in prudery— indeed, domesticity paled in importance before matters of the flesh. How white Americans, and Southerners in particular, came to think of black women as sensual beings has to do with the impressions formed during their initial contact with Africans, with the way black women were forced to live under chattel slavery, and with the ideas that Southern white men had about women in general.” (Gray White, 29).

Most alarming about the myth of the Jezebel was the necessary illusion of choice. The rate at which enslaved women reproduced was not blamed upon the circumstance of forced birth, but on their wild will for endless sex. Even speaking so plainly about their reproduction helped cement Black enslaved women as intentionally promiscuous. Black women faced with the false choice of accept their master’s sexual advantageous or be wildly punished (by rape, pubic floggings, being sold, or having their children sold) had to make whatever choice they needed to keep safe. Mixed race or light-skinned Black women were continually pimped out to white men wealthy enough to afford a “fancy lady,” often invoking the ire and wrath of the mistress of the house, who blamed Black women for their circumstance. “Many some were convinced that slave women were lustful, lascivious. that they invited sexual overtures from white men, and that any resistance they displayed was mere feigning…. Even the abolitionist James Redpath wrote that mulatto women were ‘gratified by the criminal advances of the Saxons.’” (Gray White, 30).

Eventually, white men’s unrepentant taking of bonded women proved to be complicate the morals that their ethno-state was to be guided by. How could they raise godly white children with the image of lust all around them? How can they continue to claim that chattel slavery moralizes otherwise heathenous African peoples with the Jezebels of the South roaming about freely? They refashioned the Black woman into the one closer to the myth of the white woman: someone subservient, sexless, and sinless.

“Jezebel was an image as troubling as it was convenient and utilitarian. When forced to defend it, many Southerners quickly retreated and revised their thinking. They did not necessarily abandon Jezebel nor their rationalizations of her. Rather, many Southerners were able to embrace both images of black women simultaneously and switch from one to the other depending on the context of their thought. On the one hand, there was the woman obsessed with matters of the flesh, on the other was the asexual woman. One was carnal, the other maternal. One was at heart a slut, the other was deeply religious. One was a Jezebel, the other a Mammy.” (Gray White, 46; emphasis mine)

The Morality of Mammy

Mammy was the white Southerner response to the making of the Black woman. Jezebel, for what she was worth, was far more a walking, sentient sex doll than she ever was womanly— especially because womanhood required domestic servitude and not solely sexual submission. Enter: the strength, moral backbone, and love of Mammy, the head of a white household (second to only the white mistress and her overlord husband). Mammy was surrogate mistress and mother; dedicated wholly to her white household, even before herself. She was on call day and night, with no worry to any family of her own (should she have one). She is tasked with all the unpleasantries of house management and child-rearing— commanding the kitchen, a human super Swiffer-picker-upper, a master seamstress, a dairy nurse, resident aid, tending to the sick children, white or Black. While stay in the big house came with more access to resources, it also came with increased vulnerability; in the house, there was no distance from the white man who imposed his sexual advances, nor the ire of his wife who would happily beat you for it. Even the master’s sons, who she may have nursed to adulthood, could and would take her sexually (Gray White, 48-50).

The myth of choice follows Mammy as well, that she chooses a life in the white man’s home happily over field work. In reality, Mammy was only good so long as she was useful. Part of the myth is that the Mammy figure was well-taken care of, beloved by her white family as she loved them; come old age, any Black mistress was left to her own devices after she became too old to serve. Many of these people were simply abandoned.

“Mammy knew that by becoming a friend, a confidante, an indispensable servant to the whites, she and her family might gain some immunity against sale and abuse. According to Genovese, Mammy did not always denigrate black people. She knew what was fair and proper, and often even defended black dignity, or championed the cause of the abused slave.

‘Her tragedy lay, not in the atonement of her own people,’ said Genovese, ‘but in her inability to offer her individual power and beauty to black people on terms they could accept without themselves sliding further into a system of paternalistic dependency.’” (Gray White, 55 | Genovese, 360-361; emphasis mine)

In cultural memory, Mammy became a reviled figure for Black folk from the misconception that she preferred her life of service to white masters, and that is a shame. Neither the Jezebel nor the Mammy was as preferable way of life because there was nothing to prefer; there was no choice, especially since they both came with the constant threat of violence and sexual assault. They were two sides of the same coin in trying to reconcile womanhood with blackness in order to serve whiteness.

…and some of us are brave.

Why isn’t it capital “b” Beautiful until white people do it? Why does Blackness have to get laundered by white faces, white bodies, white agendas in order to be considered marketable?

To answer the original inquiry: beautiful isn’t Beautiful until white people touch it because the the Beauty market is still 90% owned by white men. They are the makers of Beauty and still the primary beneficiaries. They are the primary creators, the stewards, and the disseminators of Beauty capital, the standardized way they purchase wives. Because whiteness is not the presence of culture but the absence of Blackness, they constantly search for something to consume, like a wayward parasite. Like lice. They desire Black women without ever wanting to credit them for their ingenuity— so they eat it, spit it back up and sell this bastardized thing on the beauty market back to the general public.

And boy, do white men want us. They justify their wants by the creation of the Jezebel, who conveniently always wants them back, and of the Mammy, who is equally as conveniently always happy to serve them their families. To date, the most marketable things one can be as a Black woman are endlessly helpful or insanely sexy. There must (read: must) be more than this for us.

Inside of beauty, we at the juncture of Black and woman fight to prove what we aren’t and embody what was made to exclude us. This history bubbles to mind when I chew on comments like, “well, why can’t we just expand the Beauty system?” It goes farther than a simple, “we can’t.” There is no expanding this to include everyone, that’s true— but I’m not even concerned with whether that’s possible. Why would I want to?

Black woman is this third space in gender where we are barred perpetually from the ease and guaranteed safety of white femininity and excluded coldly from solidarity within and across Blackness. Both these groups that should seek to reach for us, reach to love and uplift us because the combustion of Blackness and womanhood is difficult to survive, yet lights a warm hearth for many outside of us. The novel gender woman does not follow Black women neatly past the melanin in our eyes, our hair, our skin, our gums; we see, we grow, we touch, and we taste the world differently. Traditional womanhood was specifically designed to exclude and subjugate us, to punish us for advances we did not ask for and strength we wish we did not need. The strength, the quickness required to survive blackness, to grow new things within it, to fashion a culture that raises up pride, is only rewarded in men. Strength, wit, intellect, cunning are only rewarded in men. If you are a woman displaying sovereignty, you will be punished; the identity of woman is supposed to begin and end with needing men. To work endlessly for better lives is punished because men are the ones who labor. To wish endlessly for traditional femininity is to wish for the ideals of whiteness.

Yet Black cisgender women often have the hardest time releasing the relentless pursuit of Beauty. Capital “b” Beauty, which was always designed to measure one’s weight in worth; Beauty, which requires a hierarchy; Beauty which demands that you do not care who is left outside the richness of Beautiful people so long as you get invited in; Beauty which reinforces and thrives upon rejecting those outside of white gender performance as separate, distinct, unweddable— less than you, the chosen. Why?

Beauty does not justify our existence. We justify Beauty in an attempt to be everything we were told we could not be to gain protection, love, support from people that harmed us and said we begged for it. Black women long for structural access and Beauty capital is really the only way we can get it. But why do we want it?

Especially when, in this liminal space, we continue to be brave. We make and remake beauty over and over again. We innovate every expression of aesthetic we can see, touch, or taste. We are regularly the culture-makers. Black women are best kept by each other, housing within themselves friendships so intimate in their loving and so considerate in their caring they outdo husbands by landslides. There is queerness (read: deviation from the arch of heteronormativity) in centering, choosing, and prioritizing each other over all things. It is not easy; it is punished; these practices are marginalized; this being is brave.

In this liminal space of Blackness and womanness, we are an asteroid that collides with earth. The matter of stardust is everywhere. We were never supposed to happen and yet we birth ourselves over and over again, simply because we can.

We can be anything— do you follow me?— because we were never supposed to be this whole in the first place. We were never meant to be this human, much less this radiant. The worth of my Beauty, my perception of self was always meant to be owned and operated by someone else; by some white man with grimy hands reaching into my intimate space under nightfall. Why would I want his hands on my work? I can be anything. Why would I want my identity to first bend around a man, white or Black or anything? I can snatch this body back and call it mine— call it ours— and you want me to settle for training myself to want Beauty now that I can get a crumb? For watering down their colored wants? You want me to wear the pastel version of white supremacy and call that victory?

When could be anything! We could be anything.

Ismatu Gwendolyn

Sources and Recommended Reading:

Bonnett, A. (1998). Who was white? The disappearance of non-European white identities and the formation of European racial whiteness. Ethnic and racial studies, 21(6), 1029-1055.

Coates, T. N. (2015). Between the world and me. Text publishing.

Kendi, I. X. (2016). Stamped from the beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America. Hachette UK.

White, D. G. (1999). Ar'n't I a woman?: Female slaves in the plantation South. WW Norton & Company.

gorgeous piece!

Simply wonderful and informative. It was like a warm hug for my inner little Black girl.